The New Gastronome

The Witchcraft of Nixtamalization

Nixtamal the secret to pre-hispanic nutrition

by Dania Romero Mata

by Dania Romero Mata

Corn has played a central role in the Mesoamerican population for more than 3,500 years. Maize, as a crop, was domesticated at least 8,700 years ago in Mexico. The prehispanic population domesticated the corn from the ‘Teocintle’ (a wild grass) by cross-pollination until we got the varieties of corn we know today.

Maize would have been quite different without the nixtamalization process. Without nixtamalization, the vitamin properties of maize, more specifically, vitamin A, are virtually inaccessible. Deficiencies in vitamin A can be seen in a skin condition called Pellagra which was avoided by Mayan and Aztec empires, due to the incorporation of nixtamalized maize in their diets.

One of the key aspects of the diet of Mesoamerican civilization is, that it was mainly a plant-based diet before the arrival of the Spanish.

Due to the nutritional constraints stemming from a limited variety of protein-rich sources, obtaining a complete protein out of plant sources was fundamental. For this reason, the nixtamal process is essential. Basically, nixtamalization helps create a chemical change in the proteins present of the maize (corn); normally the proteins are present but not available for humans to assimilate and absorb, but through this process, essential proteins become bio-available for humans.

A. D. V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G.

The proper term of Nixtamalization comes from the Nahuatl ‘Nixtamal’; ‘Nixtli’ meaning ashes and ‘Tamalli’ meaning dough. The Nahuatl is a language commonly spoken in central Mexico by the indigenous population and has played a central role in the development of modern-day Spanish. Take for example a crowd-favourite, the avocado. The word avocado in Spanish is aguacate, which comes from Nahuatl; with just a little bit of tweaking of the spelling ‘Ahuacatl’, tada! A word is born.

“Maize would have been quite different without the nixtamalization process. Without nixtamalization, the vitamin properties of maize, more specifically, vitamin A, are virtually inaccessible. Deficiencies in vitamin A can be seen in a skin condition called Pellagra which was avoided by Mayan and Aztec empires, due to the incorporation of nixtamalized maize in their diets.“

Ok, let’s get back on track. Nixtli’ (ashes) is the core of the Nixtamal process. Boiling corn with ashes or quicklime allows the corn to soak for hours, and transform the grains into a dough mixture. This simple process creates remarkable physical-chemical changes in corn, such as increasing the nutritional value, the gelatinization of starch (makes the dough workable), the partial saponification of corn lipids and the solubilization of proteins.

I’ll take you through a chemical explanation of the process, but do not fear as there’s no final exam. Let’s talk about the chemical composition of maize. Although it changes by corn variety and environmental conditions such as soil components, on average, corn is: 70-75% carbohydrates, most of its starch, 8-10% protein, and 4-5% lipids. Now let’s get into the interesting aspect of it: proteins.

For those of us who need a bit of a chemistry refresher, I’ll give a quick recap of some of Gabriella Morini’s – my former Professor of Taste & Food Sciences class – lecture highlights.

The proteins present in corn are Albumin 7%, Globulin 5%, Prolamin or Zein 52%, and Glutelin 25% — the proteins classified for cereals. These proteins can be located in two segments of the kernel: the Germ or Embryo and the Endosperm. The Germ is located in the core of the kernel, holding the albumins and globulins (proteins) both of which are soluble in water and salt solutions. While the prolamines and the glutelins are present in the endosperm. These proteins are soluble in alcohol and alkaline solutions.

The chemical properties of the previously mentioned proteins call for a solution that would allow them to unfold, therefore making them available to break down into the amino acid pool. Humans only need a selected handful of 9 amino acids, the rest can under certain conditions be built up and/or synthesized by our bodies.

These 4 proteins present in corn are deficient in 2 essential amino acids – lysine, and tryptophan. So, missing 2 out of 9 essential amino acids is pretty good, but more importantly, it is about how much of them we can actually absorb.

Let me go back to the germ contents, which hold 78% of the corn’s minerals. Phosphorus and magnesium salts hold phytic acid in an equivalent amount of 1% of the total weight of the grain and are most abundant in the germ. Acid inhibits the absorption of essential nutrients; which is what our genius prehispanic ancestors found a way around, through the nixtamalization process. Other key minerals are Sulfur, which presents 2 essential amino acids: methionine and cysteine Iron, Calcium and Zinc. Thanks to the nixtamalization process, tortillas are a daily source of essential minerals, such as calcium in the Mexican diet.

“Long story short, the thermal-chemical process embedded with the nixtamalization process, renders vitamins such as B3 ready for the human body to digest, inhibits the function of the phytic acid, unfolds the proteins contained in the Germ and Endosperm making them ready for human breakdown without releasing them into the boiling liquid by making the starches in the kernel a sort of gelatin that holds everything in, while improving the quality of the final dough for tortilla making.“

Before we talked about phytic acid, mentioning that it blocks nutrients from been absorbed. But fear not, the kernel also contains Niacin or Vitamin B3, which can reduce the blocking effect of the phytic acid. Sadly, Niacin is not bio-available to humans in the natural structure of corn… unless the maize is pushed through an alkali thermal treatment (ahamm, Nixtamalization process).

Long story short, the thermal-chemical process embedded with the nixtamalization process, renders vitamins such as B3 ready for the human body to digest, inhibits the function of the phytic acid, unfolds the proteins contained in the Germ and Endosperm making them ready for human breakdown without releasing them into the boiling liquid by making the starches in the kernel a sort of gelatin that holds everything in, while improving the quality of the final dough for tortilla making.

There you have it, folks, the Mayans and Aztecs were on to something — corn tortillas are not only delicious but are also a source of essential minerals. As if we needed another reason to book a trip to Mexico.

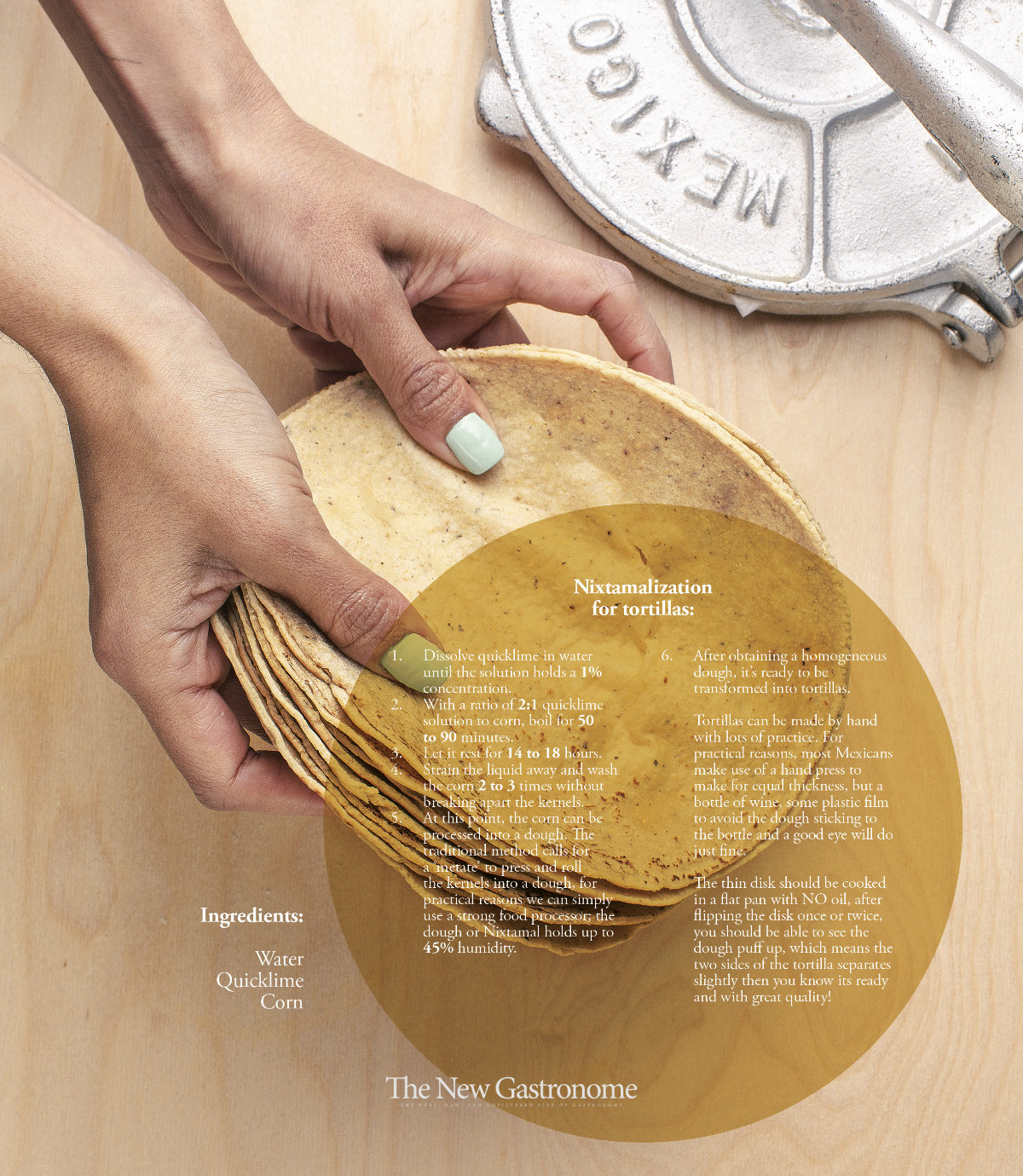

Ingredients:

Water

Quicklime

Corn

References:

Arendt, Elke K. Zannini, Emanuele. (2013). Cereal Grains for the Food and Beverage Industries. (pp. 67-104). Elsevier. Retrieved from https://app.knovel.com/hotlink/toc/id:kpCGFBI003/cereal-grains-food-beverage/cereal-grains-food-beverage

http://www.revistaciencias.unam.mx/en/41-revistas/revista-ciencias-92-93/205-la-nixtamalizacion-y-el-valor-nutritivo-del-maiz-05.html

https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/IND43969358/PDF

Photos ©Aarón Gómez Figueroa