The New Gastronome

Oranges

The Golden Apple of the Ages

by Lisa Schultz

by Lisa Schultz

The actual origin of the orange fruit is ambiguous and elusive with a long but often hidden history behind it. Exotic, rare, and expensive, oranges were a luxury item, the fruit of emperors and kings.

Coveted by the highest ranks of society, orange fruits became such a sign of opulence in the Renaissance that the quantity of oranges appearing on the banquet table measured the importance of the guests, as well as the wealth of the host. It wasn’t until the 19th century that oranges reached the tables of the middle class, and later still, that they became an accessible fruit of the community and the most popular cultivated fruit in the world. Ancient scholars believed oranges to be the “Golden Apples” of immortality stolen by Hercules from the Garden of Hesperides, the fruit sacred to Venus–goddess of love.

The Golden Apple in Italian Renaissance

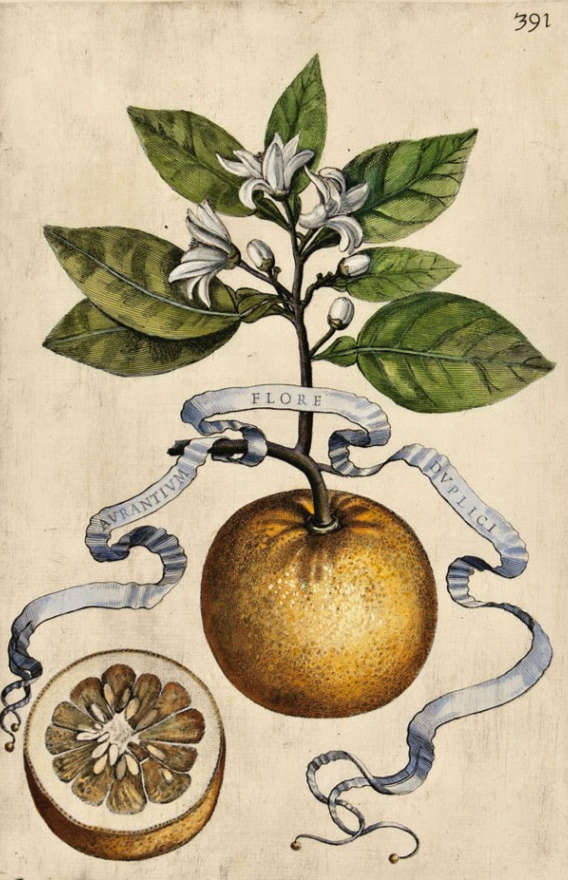

One of the most splendid, scientifically precise and decorative botanical works of 17th century Europe is Giovanni Battista Ferrari’s Hesperides, Sive, De Malorum Aureorum Cultura, published in Rome in 1646 (Figure 1). Ferrari was the first scientist dedicated to a complete taxonomic study of citrus fruit varieties, describing their origins, and documenting cultivation and medicinal uses. He enlisted the best artists of the day to illustrate the text in exacting detail.

Figure 1: “Aurantium Flore Duplici” or double-flowered orange,

Hand-colored engraving, Giovanni Battista Ferrari, Hesperides (1646).

Horticultural Advisor to the Papal family, Ferrari was appointed in the late 1630’s to manage the newly formed garden at the Barberini Palace in Rome. The famed Barberini garden displayed the newly found plants from the most recent voyages of trade and discovery. Rare plants from America, Asia, and Africa were all cultivated, showcased and named at this important Roman garden. As the title suggests, the main theme of his book was the comparison of the mythical garden of the Hesperides with the contemporary flowering of the Italian garden during the “Golden Age” of the Barberini reign.

All over the Italian peninsula architects, sculptors, painters, poets, historians and humanist scholars were commissioned to concoct a magnificent image for their powerful patrons. Equating oranges with the Golden Apples of the Hesperides, Ferrari is recalling a well-known and accepted conceit for the fruit that had been established over one hundred years earlier.

“Through Hercules, oranges became important objects of exchange, as Pontano has the hero bring the fruits to Italy to secure the gift of immortality.”

In his didactic poem, The Garden of the Hesperides, or the Cultivation of Orange Trees, composed in Naples in 1500, Giovanni Pontano provides a clever explanation for the presence of orange trees on Italian shores. Pontano’s poem combines agricultural information with mythical tales about the citrus botanical genus. He identifies oranges as the modern equivalent of the Golden Apples grown in the mythical Garden of the Hesperides.

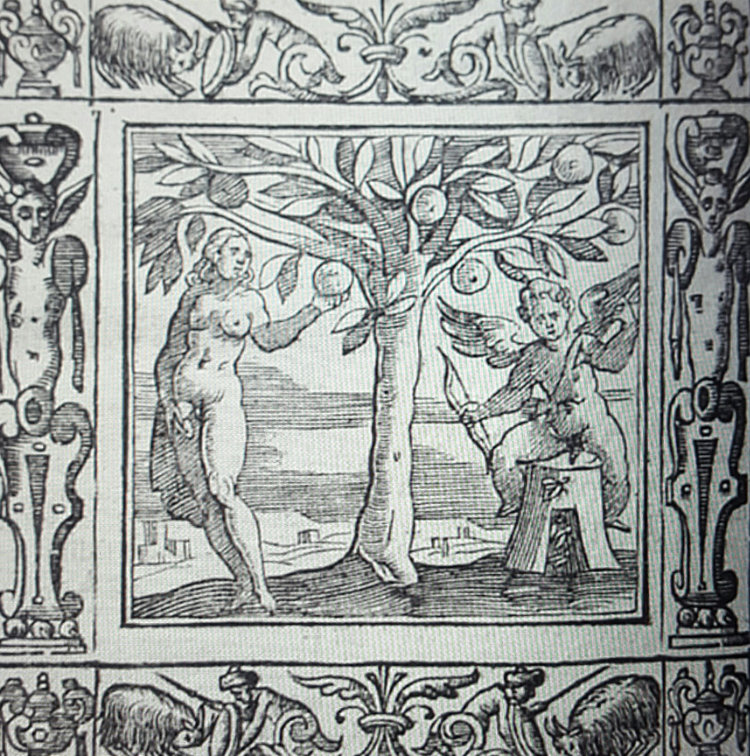

Stealing the Golden Apples was the goal of Hercules eleventh labor. Through Hercules, oranges became important objects of exchange, as Pontano has the hero bring the fruits to Italy to secure the gift of immortality (Figure 2).

Figure 2: “Farnese Hercules,”

Frontispiece to Giovanni Battista Ferrari, Hesperides (1646).

“…Venus’s fruit is the golden apple, the Orange, because the experience of love is both bitter and sweet.”

Venus, the goddess of love, also plays a crucial role in this origin story. In a bold reinvention of Ovid, Pontano recasts the myth of the death of Adonis; when her lover is killed by a wild boar and laid down in the shade of a group of laurel trees, Venus remembered Daphne, Apollo’s first love, and changed the dead Adonis into a orange tree. She planted this tree in the Garden of the Hesperides and from that moment on, the Golden Apples of the Hesperides, oranges, become sacred to her.

In one of the most important collections of emblems produced in early modern Europe, Andrea Alciati places the figure of Venus next to an orange tree; the epigram beneath the image specifies that Venus’s fruit is the golden apple, the Orange, because the experience of love is both bitter and sweet (Figure 3).

Figure 3: “Malus Medica,” in Andrea Alciati Emblematica (1621).

However, early oranges were a far cry from the sweet and juicy varieties we enjoy today. It is generally agreed that the bitter ancestor of the modern orange came from Southeast Asia. Among the first citrus varieties to arrive to the Mediterranean basin was the ancient and highly sour citron, Citrus medica.

By the first-century, citrons were well known to the Romans; Pliny the Elder reports in The Natural History that citrons were primarily ornamental potted plants; the fruits were not eaten but praised for their medicinal use, cleaning powers, evocative fragrance, and as an antidote for poisons. Images of citrons in sculptures, mosaics, and paintings found throughout the Roman Empire provide further proof of the widespread awareness of the fruit (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Roman mosaic with lemon and citron fruits from the Imperial Age. Palazzo alle Terme, Rome.

“The Arabs built intricate systems of underground irrigation channels that allowed citrus to grow and prosper throughout the arid island.”

Orange trees and their fruits, however, were unknown and unsung by the ancient poets. Sour oranges seem to have been first introduced to Italy after The Arab conquest of Sicily in the 10th century. The Arabs found the warm climate and mild winters in Sicily, along with the rich volcanic soils on the slopes and surrounding plains of Mt. Etna, perfect for growing citrus. The Arabs built intricate systems of underground irrigation channels that allowed citrus to grow and prosper throughout the arid island.

Credit is often given to Vasco da Gama for bringing the first sweet oranges to Europe in 1499. However, sweet oranges most likely reached Europe much earlier, through commercial trade routes established and maintained by the Genoese during the Crusades. In either case, an even sweeter, tastier variety arrived to Lisbon from China in 1635, Citrus Sinensi. The Portugal Orange, as it became known, is the tree from which all commercialized varieties of orange derive.

“…the mythical associations flourished across the ages, and would be exploited to the fullest by the orange industry…”

Horti Hesperidum was highly influential in establishing the prestige of the exotic orange tree as well as it’s distinctly Italian provenance; it established a distinguished mythological past for a new botanical genus that was quickly gaining popularity in modern Europe. The assimilation of oranges into the golden apples of the Hesperides was especially applicable in geographical areas where the cultivation of citrus trees was a lucrative activity, such as southern Italy and Sicily.

With a strong citrus culture already established, Sicily in particular would identify with and capitalize on this orange symbolism. Indeed the mythical associations flourished across the ages, and would be exploited to the fullest by the orange industry who astutely recognized that specific features of the island and its history, along with a distinctly regional pride of place could be illustrated, packaged, and exported.

Over the next months, we will follow that progress. We will take a closer look at the uniquely Sicilian blood orange and how the colorful wrappers that surround the fruits are linked to the Island in the Sun and its distinct regional identity.

References