The New Gastronome

Immigrants Feed America

Beyond the Statement

by Mia Frances LaRocca

by Mia Frances LaRocca

In the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, Modern Farmer debuted a printed t-shirt in an attempt to politically position themselves against the Trump administration. For the price of $24.99, you could be a walking billboard with “Immigrants Feed America” written on your front and a cascade of three quotes on your back…

“72% of US farmworkers are immigrants”

“Half are undocumented”

“Build a wall…and break our food system”

As gastronomes, we need to push beyond the statement, “Immigrants Feed America” and demand that the U.S. immigration system and the food system be redesigned to support human dignity of all people involved in the food chain. It is dangerous to perpetuate this mentality because it is founded on the premise that consumers should only care about immigration because any policy changes will affect their current access to food. This logic implies that policies should maintain the previous systems, which uphold the current dismal reality for folks involved in processing, cultivating and serving food in the United States. Instead of asking what reality will be like without the work of immigrants, let’s ask how we can demand a systematic change towards a food system that does not exploit and exclude its laborers.

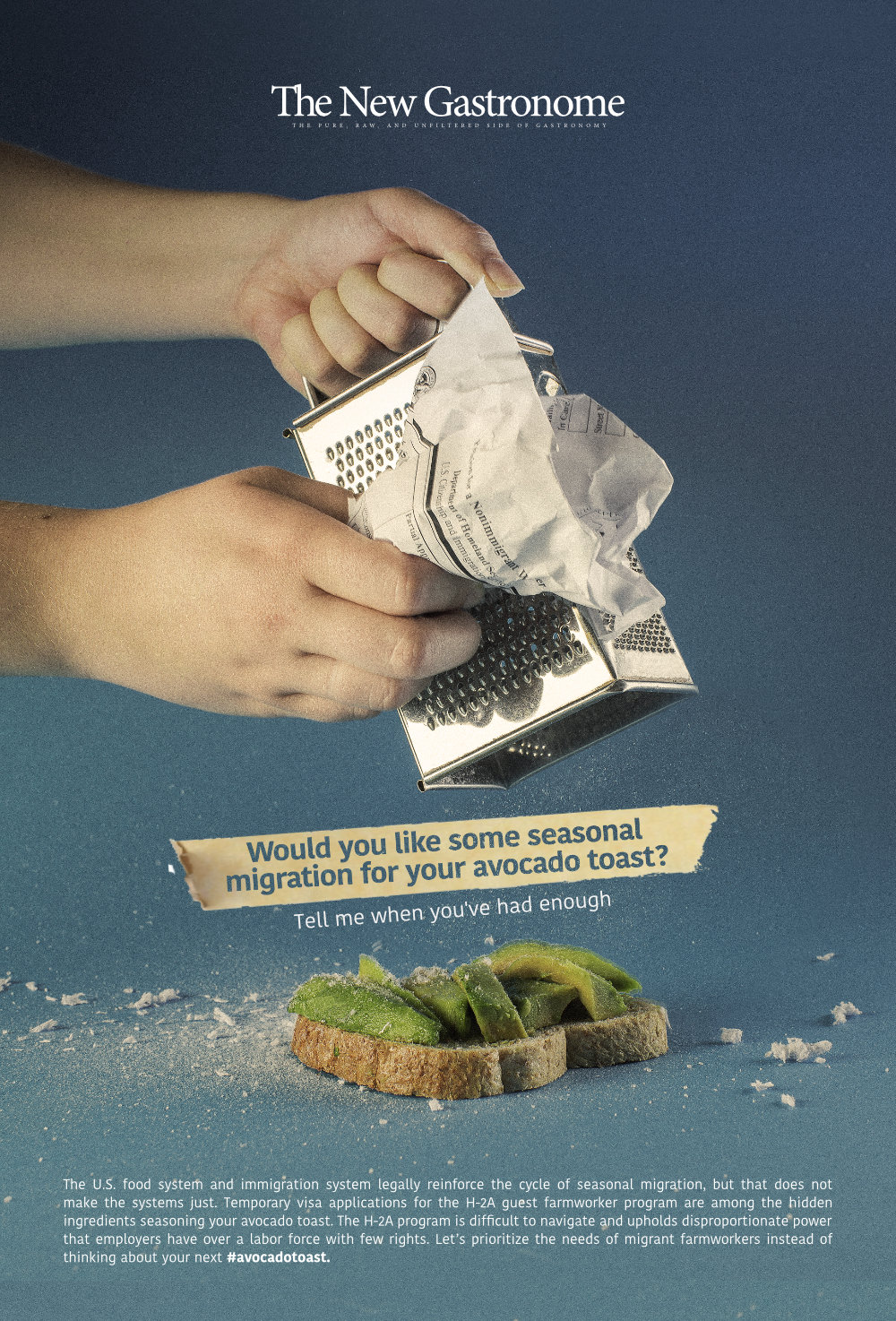

Tracing the beginning of the agricultural philosophies that drive food production in the United States back to slavery, the U.S. has always relied on different variations of migration. The links between agricultural production and slavery, created a foundation for importing labor to sustain large scale agriculture projects and normalized the idea that someone else should be producing Americans’ food so they do not have to. One of the first immigration policies that formalized this relationship was the 1942 Bracero Agreement, establishing the Bracero program as the first guest-worker program of its kind. Codifying the connection between migration and agricultural production, the U.S. relied on ‘braceros’ from Mexico to fill gaps in the fields during World War II. Although the program extended beyond the war, the use of migrant labor did not disappear with the program’s eventual termination in 1964. Rather, immigration policies evolved into more defined categories, H-2A and H-2B visas, as a result of Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 just as farms were simultaneously met with the demands of the United Farm Workers movement. Currently, H-2A visas sponsors around 140,000 seasonal agricultural workers; whereas, H-2B visas are designed to only sponsor 66,000 temporary non-agricultural workers, who are undeniably linked to the seafood industry. Even though the U.S. heavily relies on these 206,000 seasonal workers, those quotas cannot cover the demands of the current food system, so agricultural work involves unauthorized work. According to the Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey, 47% of the country’s agricultural workforce is undocumented, and these people are quite literally doing invisible work with minimal to no possibility of protection from labor abuses.

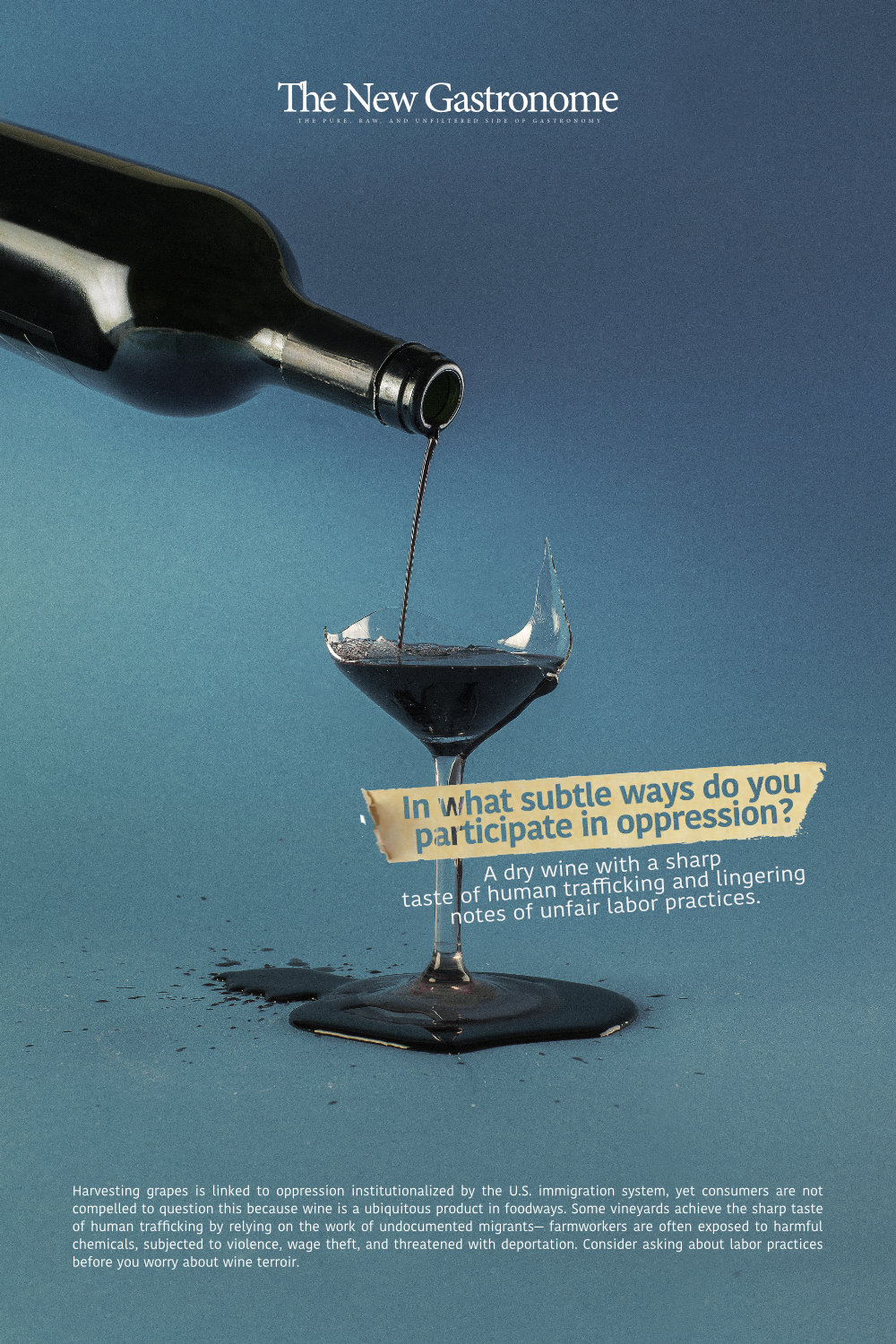

Speaking to the current reality for workers involved in processing, cultivating and serving food, there is a lot of confusion and misinformation about undocumented immigration. Not to mention that the United States is responsible for NAFTA — one of the various interventions that created the current conditions in Mexico to precipitate emigration. American media unevenly focuses on the Southern border and portrays all undocumented immigrants as originating from Latin American countries, but undocumented immigrants arrive from all around the world as a result of an outdated immigration quota system. Beyond agricultural production, immigrants are also asked to perform and satiate the part of the United States that craves foreign cuisines. Using food as a modality of integration is not always as charming as it is framed to be; xenophobic consumers can still enjoy ‘new’ cuisines without supporting the immigrant folks that provide the food for them.

The United States reinforces a terrible paradox in which immigrants, farmworkers, and many other people involved in the food industry, cannot participate in the food system that is built on their labor. Because they experience unequal access to the food system, immigrants with legal status often qualify for food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Unfortunately, rumors about the enforcement of public charge have already had dramatic consequences in the access to critical welfare programs such as SNAP, school lunch programs, Medicaid and Medicare for fear that mixed-status families will face detection and, ultimately, deportation. These severe examples of internal immigration enforcement are rooted in structural violence and prison politics because private prisons are reimbursed by the government for detaining immigrants.

“‘A Day Without Immigrants’ was a powerful reflection and encouraged expressions of solidarity, but it is dangerous to only celebrate immigrants for their abilities and contributions because they are inherently worthy and cannot be reduced to the ‘legality’ of their presence in a given territory.“

Although many representatives are outspoken advocates for comprehensive immigration reform, the government is reluctant to make a change in immigration policy because it would disrupt the entire food system. On February 12, 2017, many businesses observed “A Day Without Immigrants” to illuminate the impact that immigrants have throughout the United States. This day was a powerful reflection and encouraged expressions of solidarity, but it is dangerous to only celebrate immigrants for their abilities and contributions because they are inherently worthy and cannot be reduced to the ‘legality’ of their presence in a given territory. Focusing on the sheer functionality of migrant workers cheapens the depth of the implicit and explicit biases of immigration policies.

“As gastronomes, we need to push beyond the statement, “Immigrants Feed America” and demand that the U.S. immigration system and the food system be redesigned to support human dignity of all people involved in the food chain.”

Despite fractures in the political landscape, there are a lot of organizations fostering tangible change and disrupting complacency by using food as their medium. Countless food literacy projects, the People’s Kitchen Collective, and YARDY – to name a few – are amplifying immigrant stories and honoring their resilience. We should listen to the needs of our immigrant communities, prioritize the experiences of farm laborers, and simultaneously bolster the strength of unions like the United Farm Workers. Consumers in the United States can consider their own impact in the food system and ask how to leverage their power: by participating in alternative food systems, demanding comprehensive immigration reform to guarantee pathways to citizenship, and divesting from producers that violate human rights. Immigrants have fed America, but now Americans are responsible for restructuring the food system to set a place at the table for everyone.

REFERENCES

Research: Mia F. LaRocca | Photo Concept: Mia F. LaRocca & Aarón Gómez Figueroa