The New Gastronome

Food Flashbacks

Food before the Age of Instagram and Photography

by Master of Gastronomy: World Food Cultures and Mobility 2018

by Master of Gastronomy: World Food Cultures and Mobility 2018

For the photo project “In the Manner of…”, visting professor Yara Cluver asked her students to select a painting from before 1820, predating the beginnings of photography, with food or its consumption as a subject. From that painting, they were to create two photographs influenced not only by the painting’s subject matter and their interpretation of its meaning, but also by examining how the painter worked with composition, light, and colour. What you see here are some of the results of that assignment.

Juliana Araujo Lima

When you look at the earthy tones in the painting, the fruit seems to blend in with the soil, it is ripped apart and tossed aside. This gave me the impression that it was not to be seen as food, but as alive and part of our rotting world. The pomegranate looked like fruit at the same time as it evoked the picture of worms and larvae. I chose the rotten strawberries for this purpose and tried to capture the pomegranate torn apart, to inspire the feeling of carelessness the painting has.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

Lucca Zachmann

Cornelis De Heem portrays six prunes, four oranges, four apricots, nine cocktail cherries, four blackberries, sixty-one green grapes and twenty blue grapes on this still-life painting. These exotic and noble fruits are meticulously and sophisticatedly staged as a hanging garland. The painter’s predilection for strong blues is visible from the prunes and the blue satin bow.

Contrastingly, the shelf picture from the supermarket illustrates fifty-two plastic or cardboard multi-fruit juice containers. These every-day fruit juices are available as identical multiples, at easy access and low prices. Blue colours contrast the dominating orange tones. Concluding, a couple of noble and fresh fruits here represent a couple of processed and packaged fruit juice containers there.

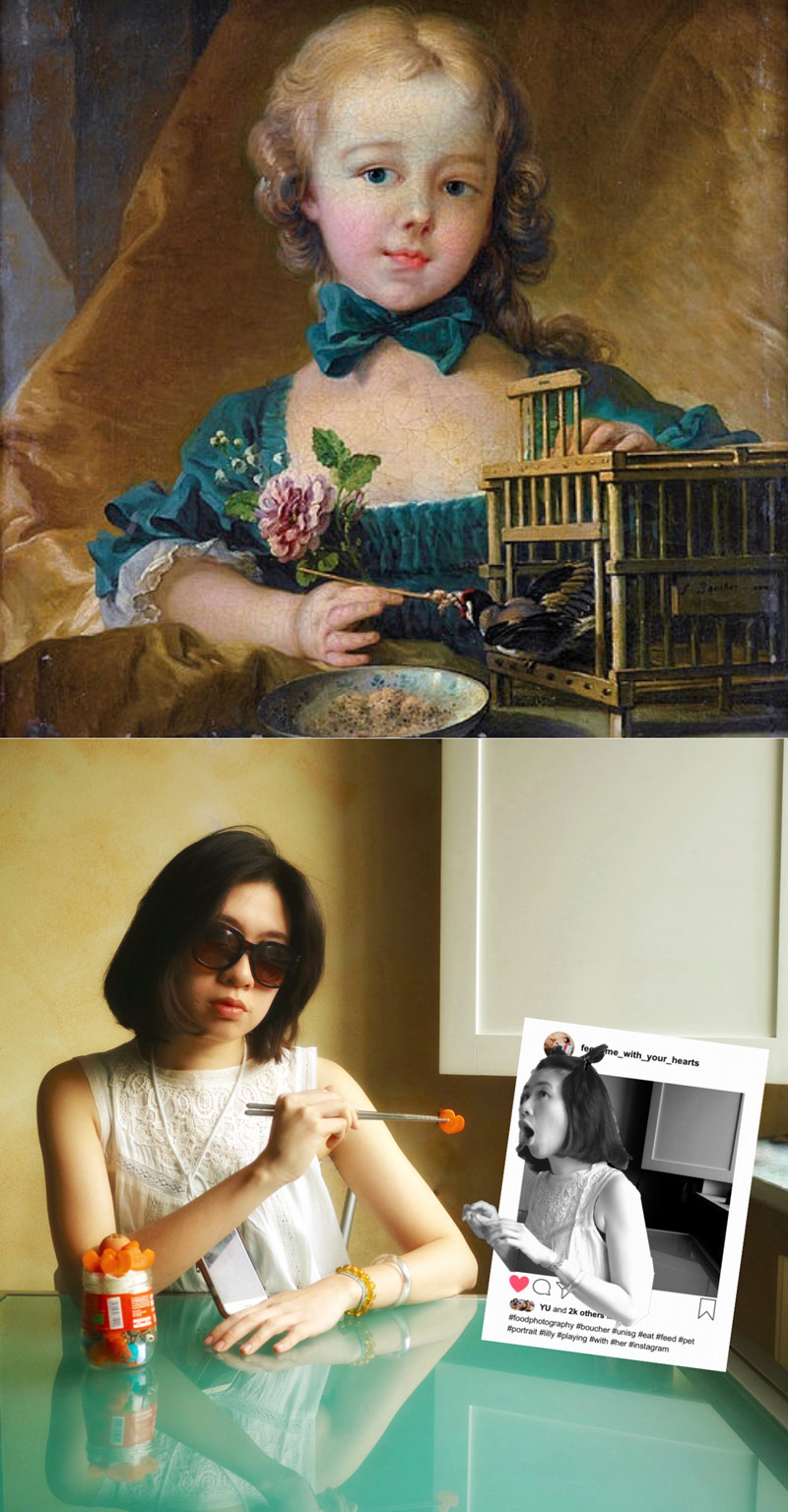

Li-Ying Yu

The background of the portrait is set indoors, maybe in a corner of the living room. There seems to be a window on her right side that provides light. The shadow of the curtain has built a depth that helps the portrait to stand out within the painting; however, Boucher’s intention to idealize the portrait has made the girl look flat with soft light outlining her – the same relationship between light and shadow can be seen on the table as well. The interesting thing is the composition, how the curtain is draped, making a triangle that points out the relationship between the three objects in the front: the girl, the goldfinch, and the plate of cereal. The food, which is used to feed the goldfinch, is not the main object but it reveals the status of the girl and the relationship between her and the goldfinch – it’s food for pets, not for people.

The audience at the time, in my opinion, was probably the girl’s parents, who wanted a painter to paint a picture of their lovely daughter. However, as a stranger who comes from another era, I saw a triangle between the pet, the girl, and her parents. First, the painting shows class, as the girl was able to have extra food to feed to her pet, instead of eating it herself. The relationship between animals and human beings are the next aspect to think about: Why does she keep a goldfinch as a pet, while chickens or ducks are considered food? The last thing that caught my eye was the theme of imprisonment. Being well dressed, having a flower and a goldfinch that belongs to nature, are somehow hinting at a desire to control nature. The goldfinch, which belongs to the sky, is caged and fed, perfectly reflecting the girl’s fate, who is also caught in the expectations of her parents, or even society.

Sara Ansell

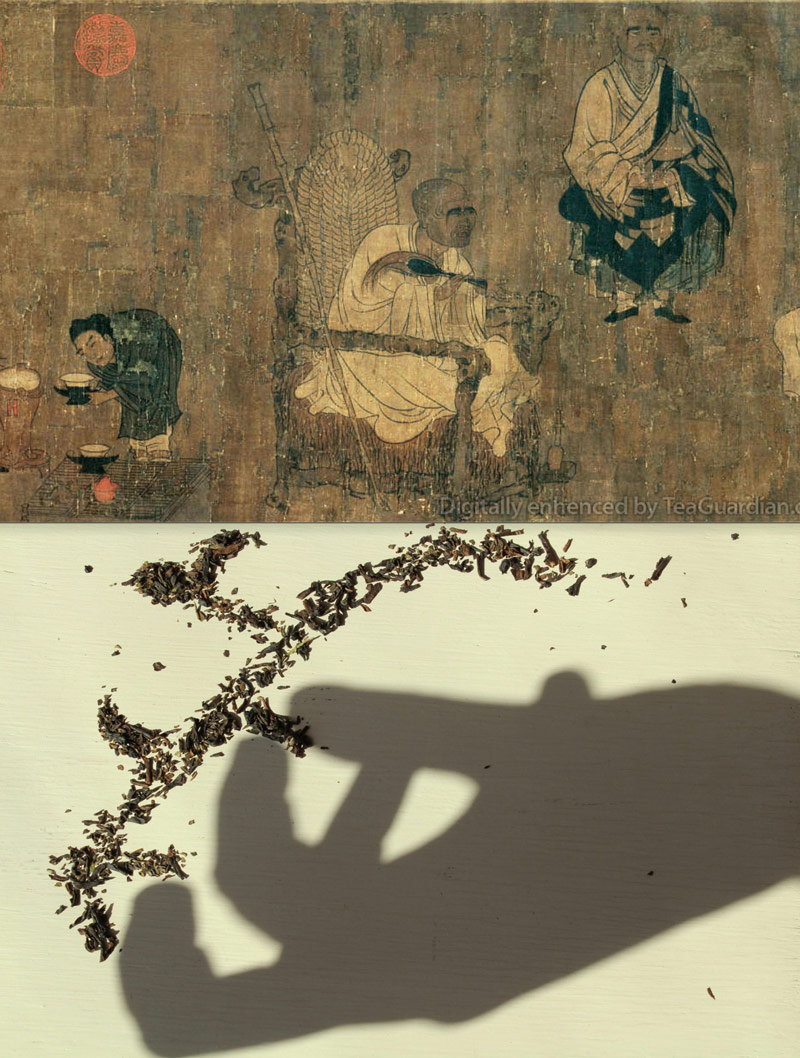

This painting depicts the story of Xiao Yi ordered by the emperor to steal the Lanting Scroll from the monks who had it in safekeeping. The composition is a simple one and to the unknowing eye, it shows a scene of hospitality. We see the tea being carefully prepared as a gesture of warmth to the guest but it is only when we know more, the sinister meaning in what is before us becomes clear. I feel that this sentiment is one that is easily translated into the tea industry today. Symbolically, a cup of tea is often a gesture of hospitality or an accompaniment to decadence but where does tea come from? Who picks it and what does their life look like? Conditions on many tea plantations are below basic human standards but how often do we think about what we can’t see and how often does that impact our enjoyment?

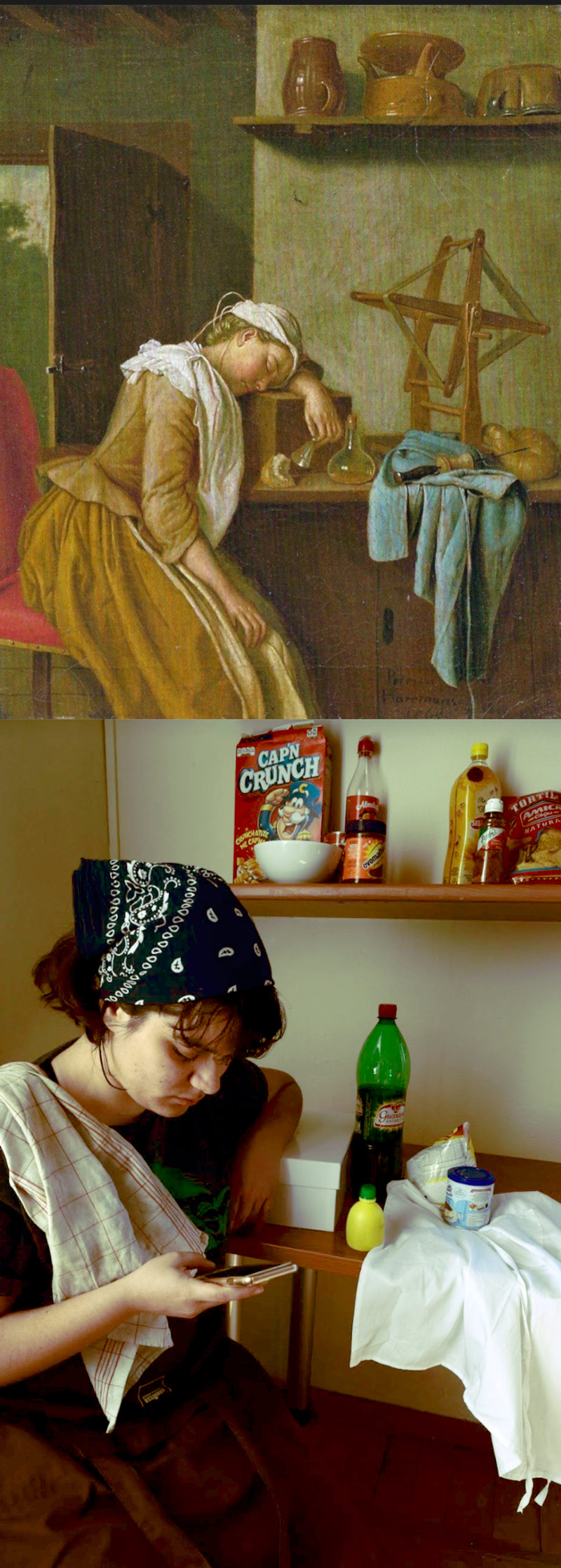

Mia LaRocca

I interpret the photo as a commentary on the lives of those doing invisible work. Artist Peter Jacob Horemans painted The Sleeping Kitchen Maid in 1765 — a time when it was common for elite families in Northern Europe to have housemaids. The contrast in this painting is striking because rather than focusing on the activities of the court that he was commissioned to paint, he elects to focus on a behind the scenes moment that does not communicate a dominant narrative associated with the elite class. Although food is scarcely present in the painting, I am drawn to the material culture of the kitchen and the complexities represented through gender and labour. In my opinion, the composure of the maid is the most provocative aspect of this painting because it seems that she was caught in a moment of rest. The food and material culture — an apron, a flask of wine, a lemon, bread, cooking pots, a wine glass, a yarn winder — in the photo suggests that she is responsible for many different tasks and provides more than just sustenance.

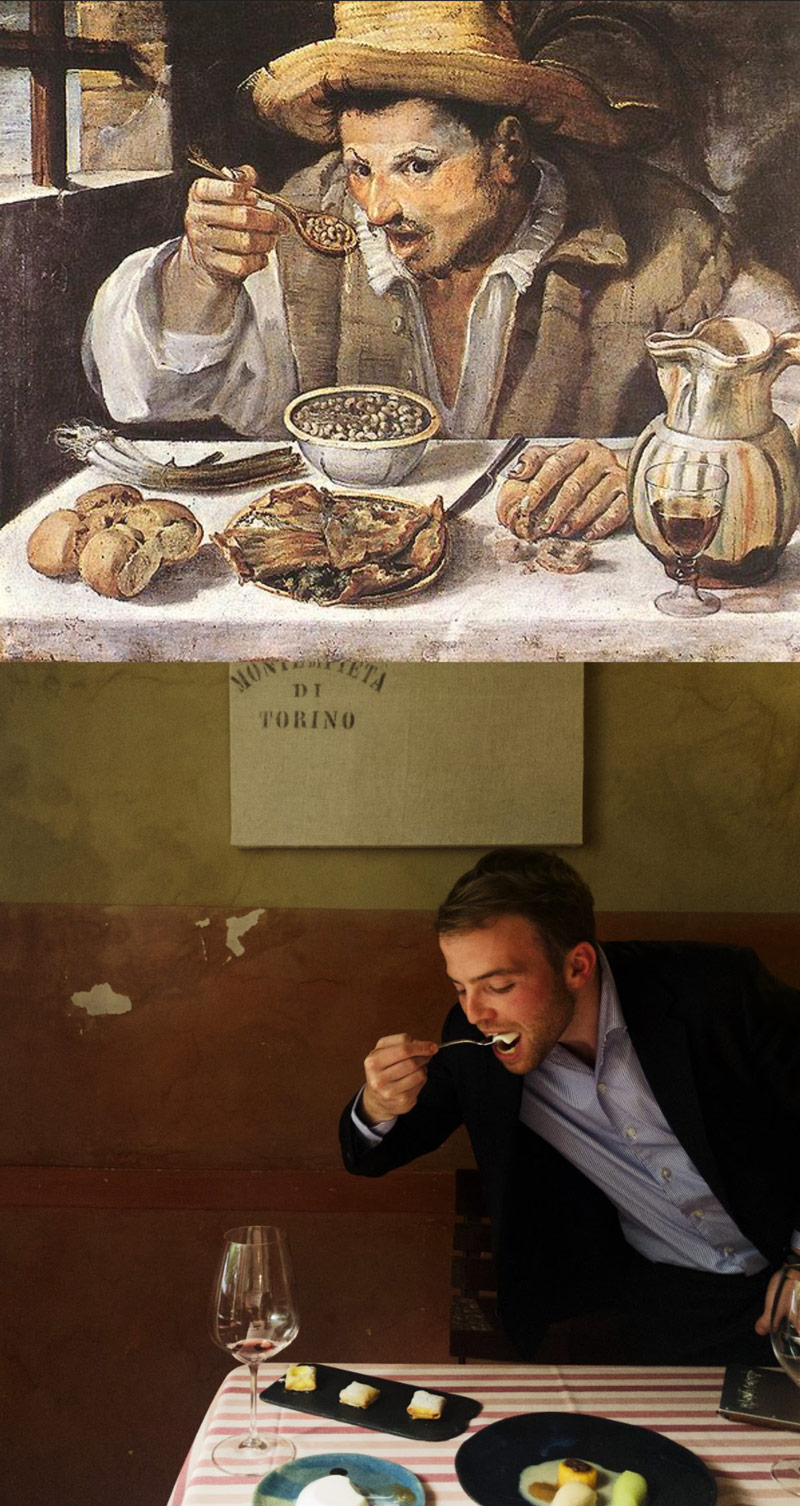

Tzu Ying

This photo shows the same vivid message as the work by Annibale Carracci’s “The Bean Eater,” the eager of eating. The local farmer, in contrast to a man in a suit. The beans contrast to a delicate panna cotta. It reveals that no matter when and which social status he has, food is always the thing to comfort and satisfy people.

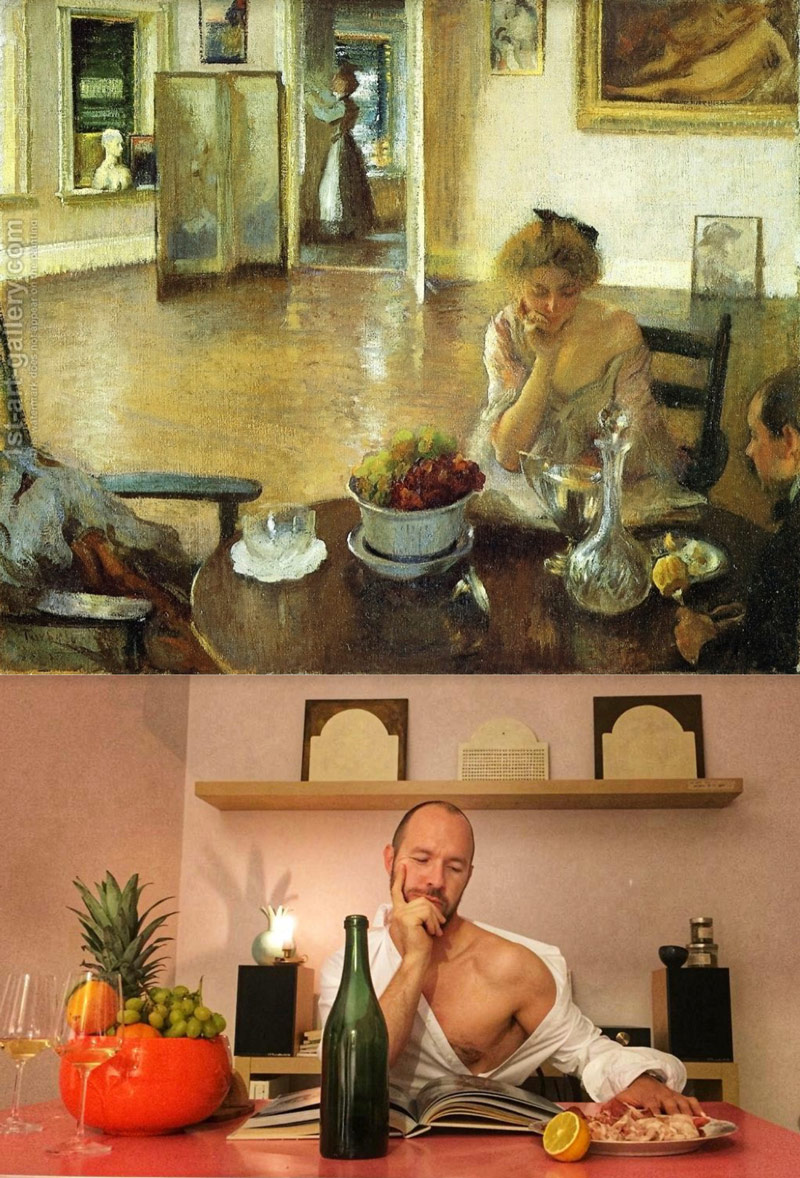

Cinta Peerdeman

In the Manner of Jean-Etienne Liotard: The main subject in this painting is not the food, but Madame Necker. The fruit has been carefully laid out to create a still life next to her. I wondered what the painting would look like after she had finished her breakfast. I took a picture of how I imagined that situation. I tried to create an image, which was too beautiful to be realistic, like the still life in the painting.

Figure 1: Lady with fruit basket, Jean-Etienne Liotard, ca. 1761

Christie Lo

Still Life with Pie and Roemer (1647) is painted during the Baroque time period, specifically the Dutch Golden Age. Looking at the painting, it gives me the impression of the aftermath of a photoshoot scene that was once perfect, with bits and pieces taken out — a scene that has just the right amount of human touch for it to seem like a part of everyday life, yet still tidy enough for it to be aesthetically pleasing. Interestingly, I feel that a lot of food stylists and bloggers today are following a similar manner of food styling; the trend is to make food appear aesthetic yet approachable in order to relate to the everyday audience. Furthermore, I believe that it is intriguing that Claesz chose to paint food in muted colours, as people usually like to make their food stand out and look as delicious as possible, almost to show-off. I believe that Claesz may have intentionally wanted to contrast a highly styled scene, rich with various foods and ornamental dishware, perhaps to counteract the highly decorative aesthetic of the Baroque period.

Andrea Pera Serrano

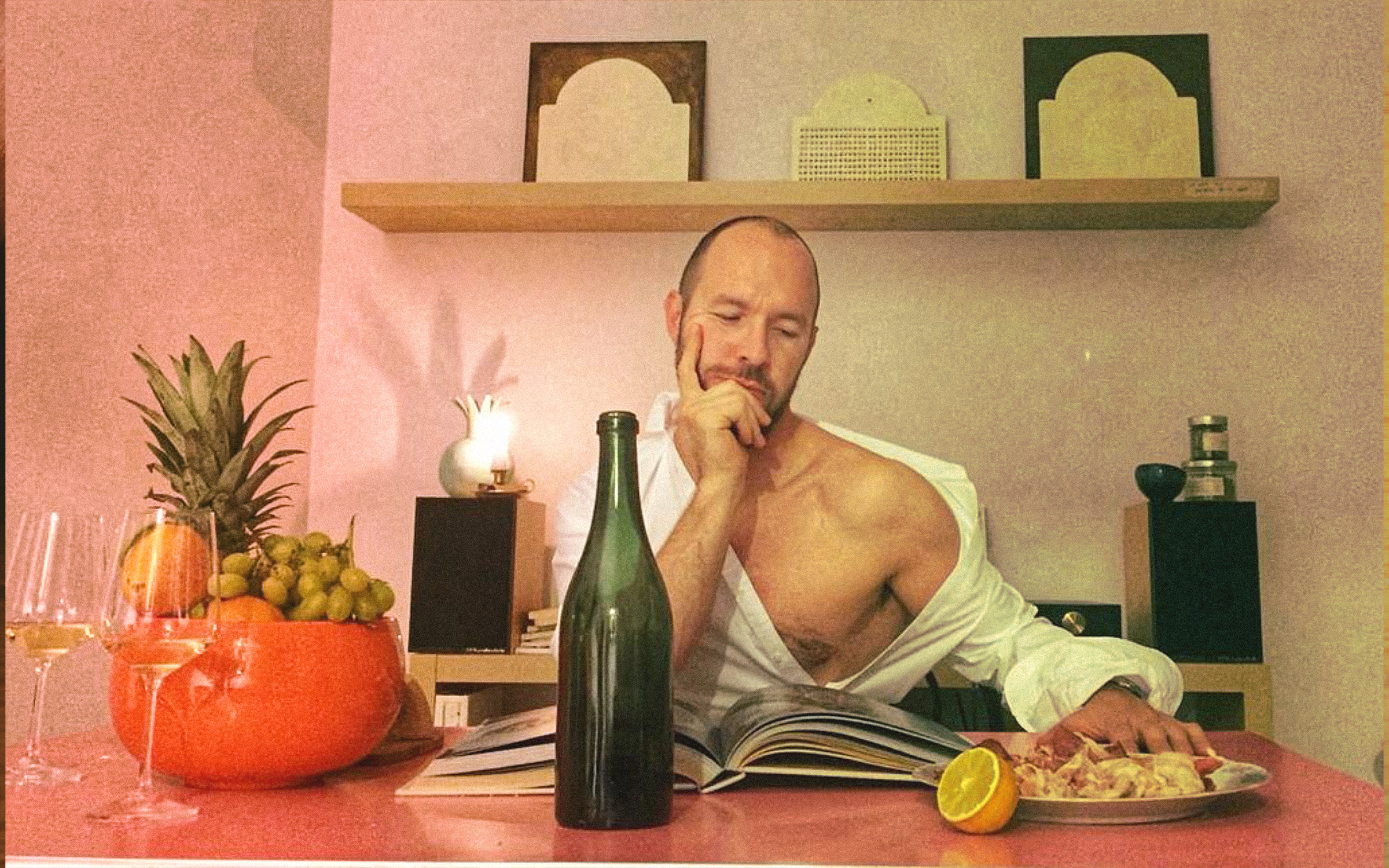

Is this image natural to you? Is it a parody? Is it futuristic? Food, gender and sexualization are common in our daily life, but they are not always obvious.

This image is a proposal for us to reflect on how normal it is for us to consume images of women and food in a sexualized way and how unnatural it looks if we use the same tools with men.

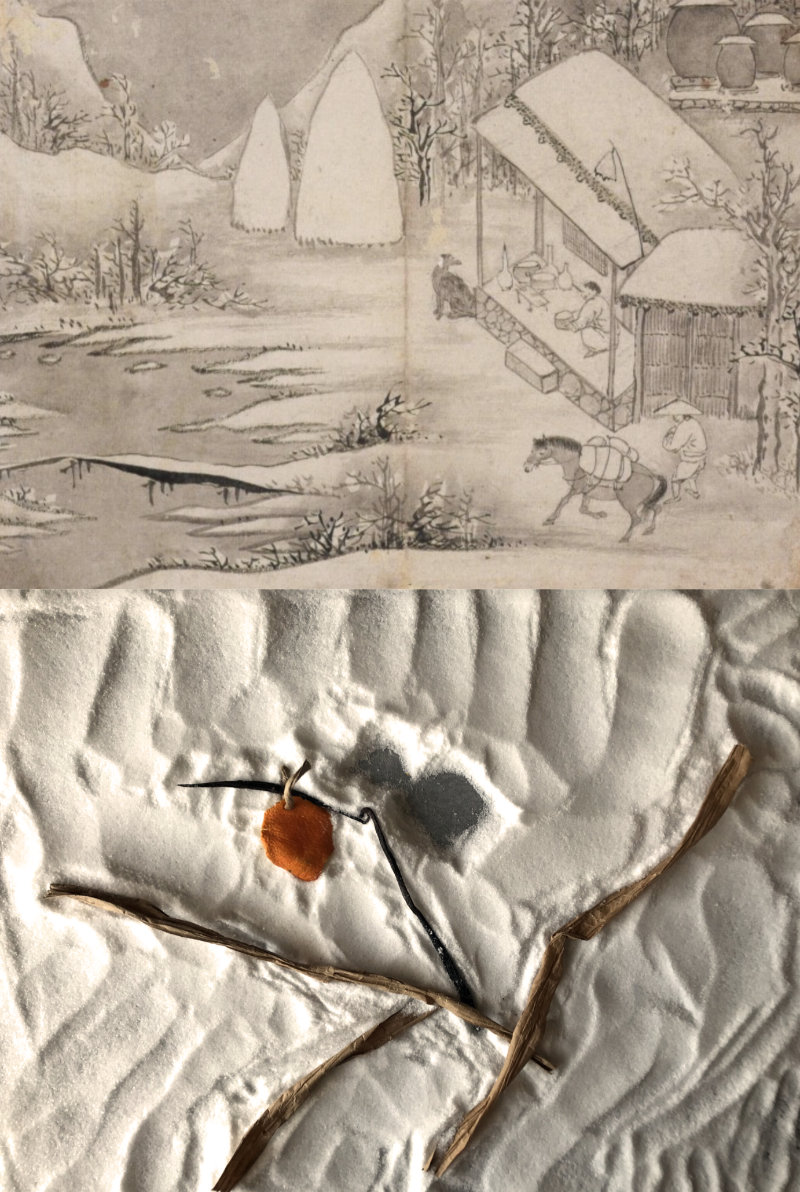

Soojin Yang

In deep winter no one is wandering around outside, but one peddler is looking for a place to stay. In deep silence, only a tiny tavern greets this cold, hungry and tired peddler. He can finally warm himself up and fill the stomach. What if a bird got tired on the way through this cold? Is there anything left for him? It seems not .. but look at that faint red thing hanging on the tree. Perhaps, people might have left some persimmons for hungry birds. This old painting reminds all of us that food is not only for humans but for all living creatures.

Tatiana Tagli

This is an oil-painted still life by Thomas H. Hope (1832-1926). A large bowl of eggs, an empty glass chalice in which to break the eggs and drink them raw: could this be the representation of the lunch of one of the first bodybuilders?

The picture – my interpretation of T.H. Hope – is rather the result of my hormones, and a sentence I heard a lot when I was in my early teens and at the school canteen. To make your food seem disgusting to you, the children who were always more hungry than the others, would tell you all the time: “Do you know what eggs are? These are the period of chickens!” This made me think about food in general and how, for some traits, we are disconnected by history or rather biology of the product. Let’s eat unfertilized ova, expelled before the embryo of these birds is formed, leaving through their cloaca; yes. These are the period of the chicken.

Rheanna Chen

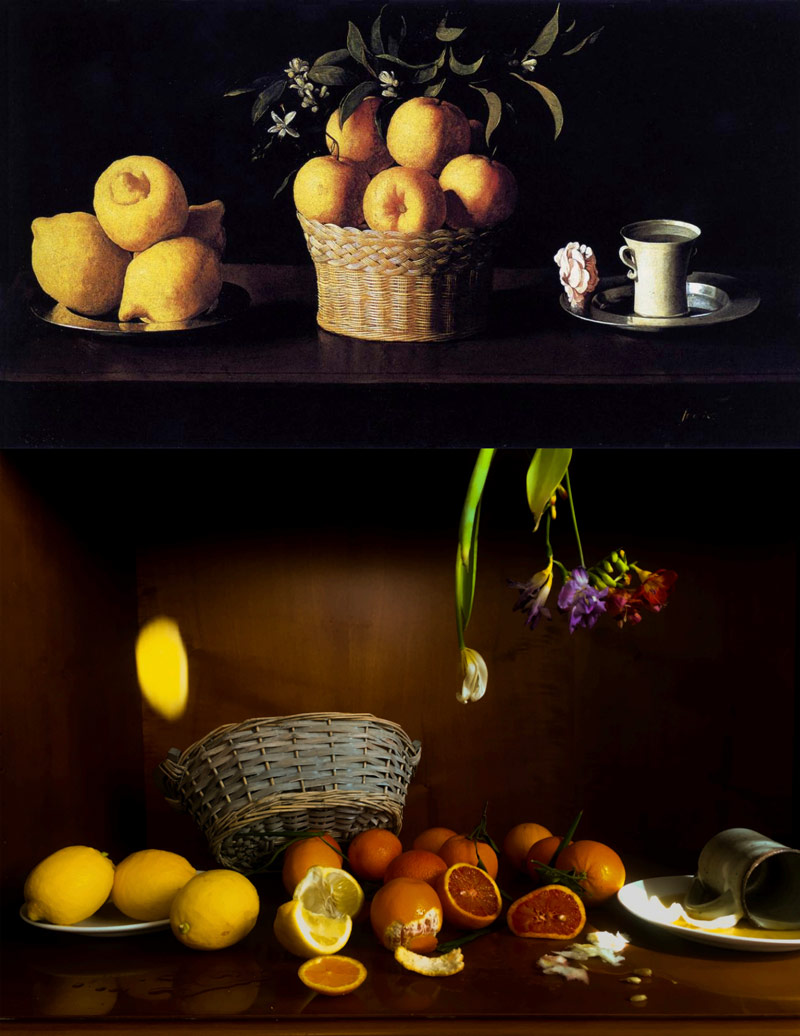

Food is the main subject in the image. Resting on a brown tabletop, either in the dining room or kitchen, is a basket filled with oranges and crowned with orange blossoms. On the right, a silver dish displays a pink rose and a white two-handled cup filled with water. On the left, a silver plate holds four citrons, whose thick, bumpy rind distinguishes them from common lemons. Presented as a quiet, almost meditative piece within minimal space, it still evokes a sense of mystery that transcends time. What stands out most to me is Zurbarán’s ability to depict the rough, textural skin of the citrus fruit and the space they inhabit. The aspects I enjoy include the balance of the objects against the dark background, the warm tones of the fruit and basket and the cooler tones of the ceramic cup and silver plates. The light coming from the left highlights the polished table surface, casting partial reflections of the citrons, the basket, and the plates. The arrangement of the orange leaves also creates a rhythm of light and shadow. It is important to know this piece is Zurbaran’s only signed and dated still life piece. To devout 17th century Spanish Catholics, the seemingly simple objects portrayed here contained significant religious meaning. The traditional associations of the individual objects encourage a symbolic reading: the citrons are an Easter fruit of faithfulness; the basket of oranges represents virginity; orange blossoms for fertility; water for purity; and the rose is a symbol of divine love. The image can be interpreted as a homage to the Virgin. Also, the structural division of the composition into three units may allude to the Holy Trinity.