The New Gastronome

Cornucopia

The Horn, the Myth, the Legend

by Lisa Schultz

by Lisa Schultz

The cornucopia, or horn of plenty, is a time-honored symbol of abundance, good fortune, and a bountiful harvest of food. Visions of abundance can be traced back from classical Greek and Roman mythology, into the early modern period, and finally into modern advertising. But along the way, the meaning has changed dramatically.

For centuries the source of cornucopian abundance was understood to be the natural world, the fertile Earth whose productive powers were celebrated and venerated in images and pagan festivals. Also, it was a vivid reminder of humans’ connection to other animals … a symbol of ecological interactions, when harmony provided a bounty. By the 15th century, the imagery of the cornucopia began to reflect the rise of mercantilism (expansion of trade, the marketplace, and the politics of commerce), which became the early stages of capitalism. The rise of the culture of consumerism and corporate advertising in the 20th century, especially in the USA, brought a literal disembodiment of traditional abundance imagery. The cornucopia remained supernaturally significant but became disconnected from the natural world …

The Origins of Cornucopia Mythology

The cornucopia, horn of Amalthea or keras amaltheias, was a common motif in ancient Greek art and literature dating back to at least the 5th century BC. While specific details of the story vary, the origin of the cornucopia can be found in Ovid’s Fasti. The she-goat nurse of the god Jupiter accidentally snapped off one of her horns on a tree and her owner, the naiad Amalthea, “picked the horn up, ringed it with fresh herbs, and took it fruit-filled to Jupiter’s lips.” According to other accounts, Zeus himself broke off the horn, gave it to his nymph nurses, and endowed it with great powers so that it would instantaneously become filled with whatever the possessor desired.

As the myth illustrates, the cornucopia is a symbolic vehicle by which nature provides her abundance to mankind, and its power to bestow prosperity was closely associated with female deities of agricultural wealth. In agrarian societies such as Greece and Rome, religion was a powerful force and man’s reliance on the earth, his gratitude for her abundance, was richly illustrated. Statues, coins, mosaics, vase and wall paintings provide visual evidence of nature worship as an essential and integral part of daily life. Classical writers and poets further reinforced the connection between heaven and earth, enumerating the many agricultural feast days that must be observed, extolling the virtues of various goddesses and the shrines built in their honor, while also giving advice on how to best please the Gods to earn their favor. The myth of the origins of the cornucopia illustrates the permeability of boundaries between nature and culture, matter and spirit, human and divine. In the animistic society, the power of images granted them a life of their own. The statues were not merely representations – they were understood to embody the deity. Proper reverence must be made to receive the gifts they control.

“The myth of the origins of the cornucopia illustrates the permeability of boundaries between nature and culture, matter and spirit, human and divine.”

Tyche was the Greek goddess of fortune (Fig 1) but she was also the personification of a concept that both intrigued and inspired ancient Greek poets, philosophers, writers, and artists. This concept combined not only fortune, but also luck, success, or even chance. In Roman mythology, Tyche was called Fortuna. Because of the many aspects associated with her, she was one of the most popular and important goddesses of the ancient world and magnificent temples were built in her honor. The primary attribute of Fortuna is the cornucopia she holds in her arms, or sometimes tips upside down, spreading the riches across the land. In addition, she often holds a helmsman rudder by which she steers the fate of men. Fortuna was fickle and could bring either good or bad luck. As such, respect and reverence to Fortuna did not disappear with the ascendancy of Christianity in the Middle Ages. However, the cornucopia, the vehicle by which she distributed her abundance to mankind, would be redefined and reinterpreted.

Fig. 1: Fortuna, Roman reworking of a Greek original of the 4th century BC. Head is not original. Ostia. Pio-Clementino Museum, Vatican City.

Commerce and Cornucopianism

With the rise of the European city-state and the increased movement and exchange of goods provided by developing maritime commercial societies, the close relationship between man and his natural environment begins to disappear. Advances in technology mean greater control over the environment, greater yield, and a surplus of product. In turn, there is less dependence on the environment and greater attention is paid to non-agricultural pursuits. The expansion of commerce and the establishment of a monetary system of exchange complete the transition from the former agrarian society to one based in commercialism. While the western European marketplace between the thirteenth and fifteenth century was characterized by locally produced goods traded over relatively short distances, highly urbanized cities like Florence, Genoa, Venice, and Antwerp became vibrant trade centers and food for the growing merchant class was mostly imported. In addition to staple goods and necessities, a bewildering assortment of luxury products from distant and exotic places became widely available. Thus the marketplace became an ever-increasing source of abundance in the 15th and 16th centuries, and the image of the cornucopia was a powerful tool of political and social propaganda. The horn of plenty, its rich content of fruits and vegetables, would remind the viewer of the bounty of a thriving marketplace, the prosperous city and beneficent government that made it all possible.

In 1428 the city of Florence erected a colossal statue representing Dovizia, or Abundance, in Mercato Vecchio, the city’s open-air market. Commissioned from Donatello, the statue was placed high on an ancient column pediment at the entrance to the market, positioning the image as a dramatic emblem of civic identity and landmark of Florence. Abundance is shown with the standard classical attributes of the cornucopia and a basket of fruit (Fig. 2 & 3). Although quite pagan in appearance, in the Renaissance era of rebirth of Classical thought, she would have a Christianized association with civic wealth and charity. The fact that this was a civic commission in a very public location, hints at political motivation. Indeed the Mercato Vecchio was built on ancient Roman foundations and linking Florence to Rome was politically advantageous at that time. But more importantly, the statue was an overt display of civic wealth and charity. Its presence was meant to remind citizens of their government’s beneficent rule. Not unlike ancient Roman state charity, Florence’s resources were being channeled into her subjects’ well being.

Fig. 2: Anonymous. View of the Mercato Vecchio in Florence and the statue of Dovizia by Donatello on antique column pedestal. Calenzano Betini collection. Kuntsthistorisches Institut.

Fig. 2: Anonymous. View of the Mercato Vecchio in Florence and the statue of Dovizia by Donatello on antique column pedestal. Calenzano Betini collection. Kuntsthistorisches Institut.

Fig. 3: Detail of Dovizia.

Fig. 3: Detail of Dovizia.

Cornucopianism in the 20th Century

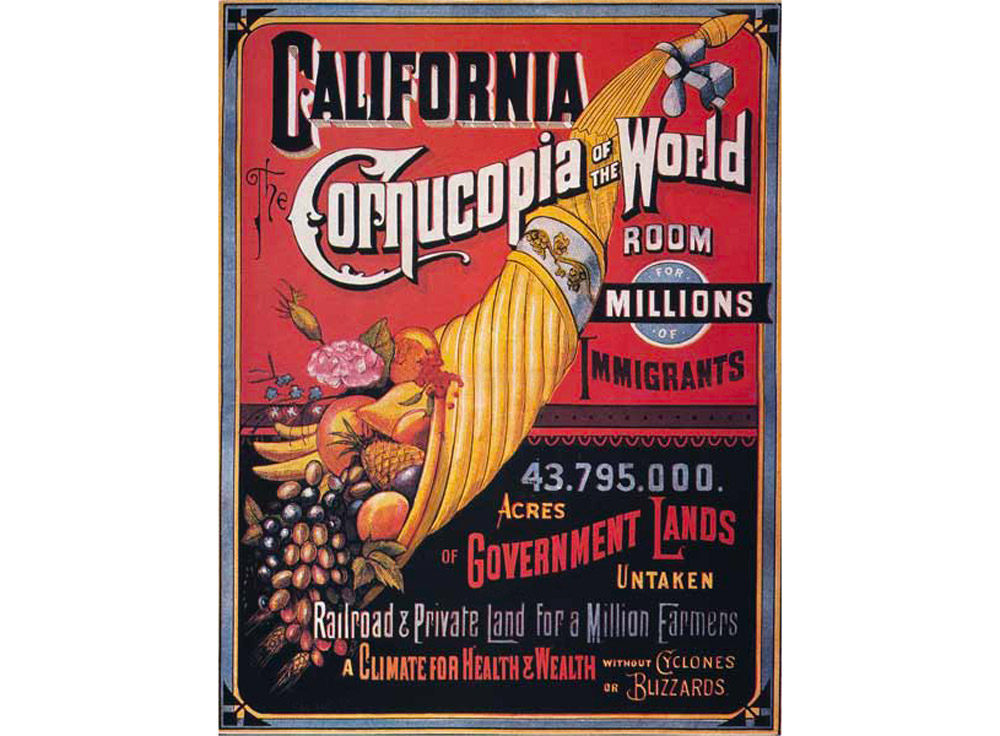

In the industrialized world of the 20th century, the cornucopia as a powerful and miraculous source of limitless abundance reappears as the perfect symbol to promote the growing culture of consumerism. Print advertisements feature cornucopias overflowing with all manners of worldly goods ranging from the traditional fruits and vegetables, nuts, grains and flowers, to biscuits, typewriter ribbon, rotary telephones, even automobiles, tires and beyond (Fig 4). Cornucopias were used in advertisements to promote the railroads, the auto industry even the State of California, the “Cornucopia of the World” with “room for millions” (Fig. 5). While the supernatural significance of the cornucopia remains intact, there is a drastic shift in the imagery. Now the cornucopia works its magic alone – the figural personification representing the origin of the goods is no longer present. The hand of the maker becomes invisible as production is severed from consumption. Instead of nature, Mother Earth, it is now the factories and machines that supply the endless bounty.

Fig. 4: Baby New Year 1944, atop a horn of plenty that spills forth all sorts of goods.

Fig. 4: Baby New Year 1944, atop a horn of plenty that spills forth all sorts of goods.

Fig. 5: California, Cornucopia of the World, broadside, 1883, RB 248676

Fig. 5: California, Cornucopia of the World, broadside, 1883, RB 248676

“Now the cornucopia works its magic alone – the figural personification representing the origin of the goods is no longer present. The hand of the maker becomes invisible as production is severed from consumption.”

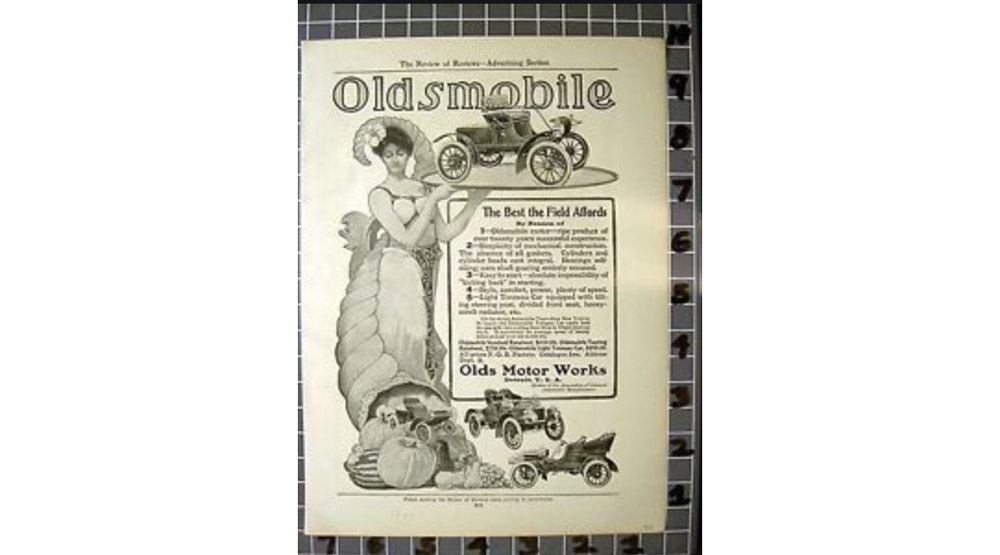

The disembodiment of abundance imagery involved a movement away from the ancient’s interpretation of female as the source of plentitude. In developing the new corporate iconography women were reduced to purchasing agents and managers, or more commonly to mere passive consumers of the stuff generated by the male genius of mass production (Fig 6).

Fig. 6: Female sales girl and a cornucopia spilling forth Oldsmobiles in an ad from 1904.

This association reaches its fullest effect when applied to the imagery of the newly pioneered concept of the supermarket. Publix was founded by George W. Jenkins, the son of a rural Georgia grocer, in Winter Haven, Florida in 1930. By 1940 Jenkins had opened his first supermarket, an 11,000-square-foot “food palace” featuring innovations such as a paved parking lot, air conditioning, wide aisles, automatic-eye electric doors, and open dairy cases. The aesthetics and features of Jenkins’s superstore were unusual for American grocery stores during the Depression, reflecting the founder’s attempt to make “shopping a pleasure.” In the mid-1950s Jenkins hired a local artist, Pati Mills, to create hand-painted ceramic tile murals to be placed on the exterior entry walls of all new Publix stores across the state. Over 200 murals were installed over the course of nearly 25 years. The common theme in these murals was a gigantic cornucopia that showcased the local bounty of products to be found within the store (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7: Publix mural. Photo: ©Rick Stepp.

Fig. 7: Publix mural. Photo: ©Rick Stepp.

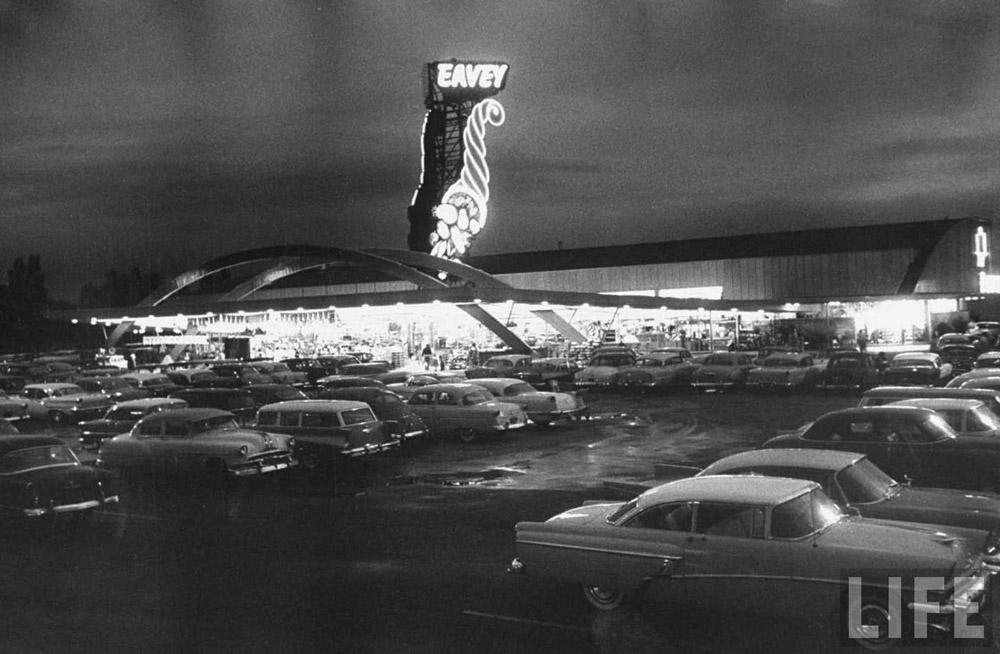

Consider also Henry J. Eavey’s flagship store built in Fort Wayne, Indiana, 1957 – at 80,000 square feet, it was the largest supermarket in the world at the time and was even profiled that year in Life Magazine. Eavey’s revolutionary store featured “turning spits and burbling bean pots” and “all the roastin’ ears you can eat for 5 cents.” Surrounded by a 10-acre parking lot and topped by an 80-foot-tall sign (Fig. 8), the store was described as “the Taj Mahal and the Farmer’s Market, and Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey – only bigger.” A looming neon cornucopia provided a beacon to shoppers for miles around, signaling an oasis of goods and services that could be found beneath.

Fig. 8: Eavey’s Largest Supermarket in the World, 1958, Image from Life Magazine feature.

Fig. 8: Eavey’s Largest Supermarket in the World, 1958, Image from Life Magazine feature.

Supermarkets offered modern convenience, they provided a larger selection of goods, plus they could offer lower prices compared to older-style grocery stores. Processed food exhibited on supermarket shelves became a metaphor for the political, economical and cultural supremacy of the United States. Highly processed food, and the individual choices afforded by the self-service shopping, intentionally correlated “Americanness” with large quantities of food, a symbol of personal affluence as well as an effective supply model. Americans were encouraged to view themselves in terms of abundance and plenty. However, any interest in the origin, the source of all this abundance, was lost. This severed connection between producer and consumer is mirrored in the modern image of the cornucopia, which now stands alone as a standard American icon of abundance. The female, her spiritual connection to the earth, is removed from the meaning. In a modern industrialized world, the source of plenty is understood to be the factory, the realm of man.

“Processed food exhibited on supermarket shelves became a metaphor for the political, economical and cultural supremacy of the United States.”

This phenomenon was not only limited to the United States. A final example of how the cornucopia’s original meaning has been obscured over time, resulting in an ever-increasing level of human disconnect with the environment and the source of its bounty, is the Rotterdam Market Hall. The complex combines the idea of the traditionally covered marketplaces found throughout Europe, with modern high-end residential living space. It contains over 100 food stalls, a gigantic commercial grocery store, 8 restaurants, and the city’s largest parking lot. But what is most fascinating about the building is that inside it is adorned with an 11.000 meter-square artwork by Arno Coenen, called Hoorn des Overvloeds (Horn of Plenty). The artwork was made using digital 3-D animation printed onto 4000 perforated aluminum panels and depicts a panorama of supersized fruits, vegetables, seeds, fish, flowers and insects that all appear to tumble from the sky into the market stalls below giving the impression that the bounties of the earth magically appear from the skies and tumble right into the marketplace (Fig 9). The Rotterdam Market Hall is, in effect, a giant cornucopia (Fig. 10). It is a bounty built by technology and we are completely integrated and surrounded by the results.

Fig. 9: Detail Of Rotterdam Market Hall, Arno Coenen, Hoorn des Overvloeds (Horn of Plenty). SOURCE: https://www.dailytonic.com/markthal-rotterdam-by-mvrdv-nl/

Fig. 9: Detail Of Rotterdam Market Hall, Arno Coenen, Hoorn des Overvloeds (Horn of Plenty). SOURCE: https://www.dailytonic.com/markthal-rotterdam-by-mvrdv-nl/

Fig. 10: Rotterdam Market Hall. SOURCE: www-mvrdv-nl

Fig. 10: Rotterdam Market Hall. SOURCE: www-mvrdv-nl

The significance of imagery depends on the cultural setting, and changes in established imagery reflect a change in cultural values and attitudes of the society that produced them; certain cultural values are sanctioned over time, others marginalized or even made invisible. Because of the longevity and universality of the cornucopia as a cultural icon in the Western lexicon, modifications in the way it is depicted and interpreted are culturally revealing. The relationship to the material world is recast; the integral connection that once existed between man and nature, producer and consumer, is modified, obscured and ultimately severed. These adaptations to the cornucopia as a symbol of earthly abundance mirror the dominant cultural values – the social, political, and economic aspirations – most relevant at any given time.

A Return to Original Understanding of the Cornucopia

In the twenty-first century, an increasing desire for locally and seasonally grown food, artisanal products that are good, clean and fair, the rise in home gardens and our fondness for producing meals from scratch all signal a fight against the sense of alienation developed from mass-produced industrialized food and the lost connection to the producer. The growing local food movement not only represents a rejection of industrial foods but also represents an emerging vision of a fundamentally better food system of the future, one that is able to sustain a common sense of ecological and social integrity built from personal relationships of trust and confidence.

But, as evidenced by the Rotterdam Market Hall above, this culture is still a minority. The transformation of the food system is but a part of a transformation in society as a whole that is about mindfulness, integrity, and authenticity. Perhaps the creation of a new sustainable and local food system, a return to more harmonious method of growing, cooking and eating will help restore and awaken a lost spiritual connection with the land, with our food, and with each other. The imagery at that time will no doubt reflect this evolution.

Acknowledgements

My sincere gratitude goes out to Krishnendu Ray and Rick Stepp for their generous support, insightful comments, and outstanding contributions to this article!

References

1. The ancients appear to be uncertain about the nature of Amalthea; according to some traditions Amalthea was the goat who suckled the infant Jove. In other traditions, she was a nymph who fed Zeus with the milk of a goat. Jupiter or Jove was regarded as the Roman equivalent of the Greek Zeus, ruler of the gods, god of sky and thunder. Various tales of the origin of the cornucopia can be found here: https://bit.ly/38s4U04 and here: https://bit.ly/2IsGWXK

2. Ovid’s Fasti, Book V, May 1.

3. Represented in coins, art, and literature as Demeter, her son Plutus, Cybele or Ceres, but can also include Tyche, and related personifications of Abundance, Fortune, Hospitality all of whom bestowed earthly bounty and riches via the cornucopia.

4. Lears, p. 21

5. One of the finest is the temple at Praeneste outside of Rome, but important temples were also in Rome’s Forum Boarium and in Antium.

6. Braudel, F. and Reynold, S., The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism, 15 to 18th Century, Berkely, CA, University of California Press, 1992.

7. By placing the statue high on a column Florence meant to emulate ancient Rome, specifically the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius. But it would also recall the statue-topped columns at the entry port of the busy maritime trade center of San Marco in Venice.

8. See Wilk, p. 21-27 for her links to Trajan’s charitable program of Alimenta, and its evolution to images of Christian Charity in Renaissance.

9. See summary of Karl Marx “consumer fetishism:” https://bit.ly/39toPNi

10. Lears, p.19.

11. International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 31. St. James Press, 2000. http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/publix-super-markets-inc-history/

12. Food in Time and Place: the American Historical Association Companion to Food History, Paul Freedman, Joyce E. Chaplin, Ken Albala, University of California Press, 2014.

13. Please see the blog post: Six Reasons Local Food Systems will Replace Our industrial Model, May 18, 2017, inthesetimes.com, by John Ikerd. Accessed February, 2018.