The New Gastronome

Potato Pete

Britain’s Unique Propaganda Strategy

by Dominic Van Asseldonk

by Dominic Van Asseldonk

A weapon of war, available to the masses; a symbol of unity and solidarity; a saviour for days of great scarcity. It is not often that praising words like these are directed towards the potato. From being declared the national food of Prussia by Frederick the Great (playfully nicknamed the ‘Potato King’1) in the 1750s, to taking the lead role in the Great Famine of Ireland in the 1840s2, the potato, undoubtedly, has become well-known in European food history.

Although it was widely looked upon with suspicion when first introduced by the Spaniards in the 16th century3, the potato has managed to settle itself as an important staple across the European continent. It has fed many mouths and has become an essential source of energy for countless people. But, until the second world war, it had never been more than that. Who would have thought that in the war-struck Britain of the 1940s the potato would rise to become the protagonist in a brilliant piece of propaganda? With the help of the Ministry of Food, the humble potato became a rock for the British people to hold on to. A weapon to draw. A ray of light for days most dark.

In the 1940s, Britain was at war. At sea, the Battle of the Atlantic between the Allied and Axis powers raged4 and Britain depended heavily on ships for the import of industrial products, oil, and most importantly, food. Before the beginning of the war, Britain imported a good 60% of its food. Germany, later assisted by Italy, was very much aware of this and attempted to disrupt this crucial supply chain. The food supply line was pinched, and a nationwide famine was lurking. With World War I fresh in their memories, Britain was quick to respond. Rationing became the standard. To ensure enough food, and to keep the morale high, the enormous ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was set up with the aim to motivate the British people to grow their own vegetables. Even the lawns outside the Tower of London were turned into small vegetable gardens5.

Leaflets were an important part of the campaign. They contained all sorts of phrases and rhymes, aimed at motivating people to ration and to grow their own food. One such rhyme directly appealed to peoples’ loyalty toward their government and country: “Those who have the will to win, cook potatoes in their skin, knowing that the sight of peelings, deeply hurts Lord Woolton’s feelings.” Lord Woolton was the Minister of Food, and the one responsible for establishing the rationing system6.

“To ensure enough food, and to keep the morale high, the enormous ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign was set up with the aim to motivate the British people to grow their own vegetables.”

Many previously imported foods did not grow in Britain, and even bread became scarce because of the country’s dependence on imported wheat. Thus, an important part of the Ministry’s famine-prevention strategy involved convincing the people to like the food that was already available.

And so, along came Potato Pete.

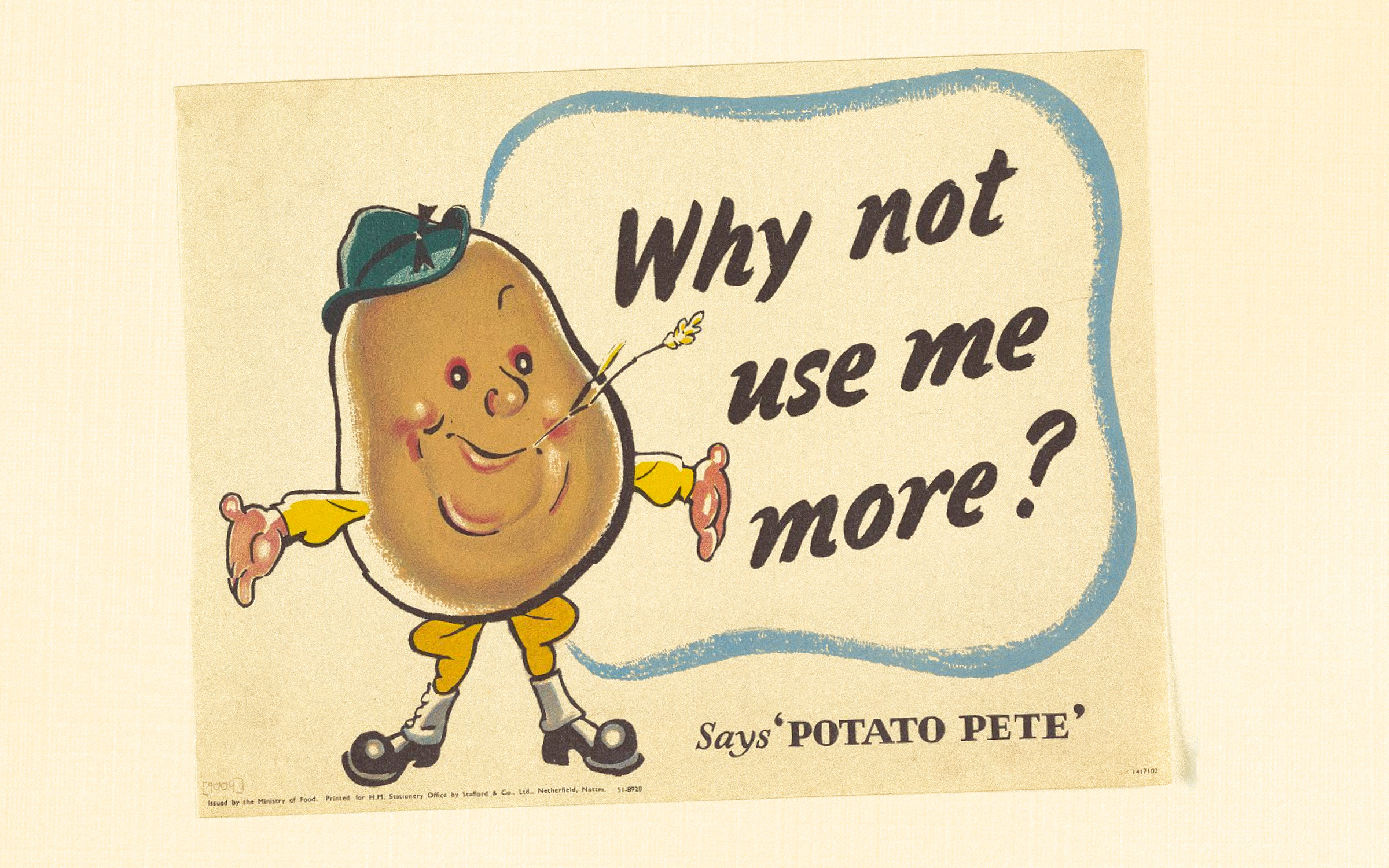

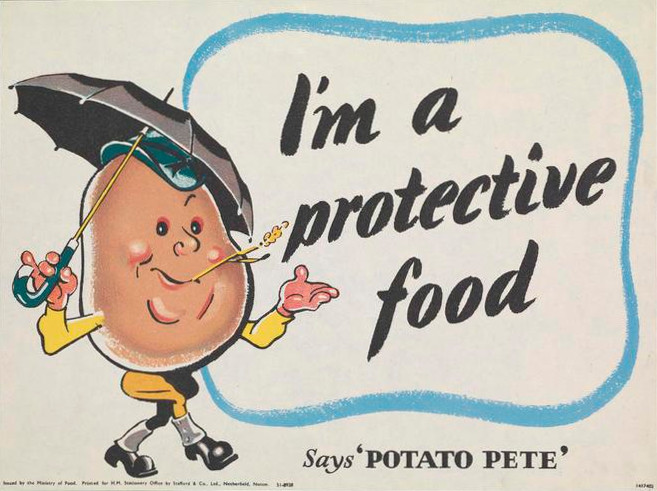

Potato Pete was a cartoon figure used by the British government to get the people to eat more healthily and sparingly. Pete appeared on leaflets, the radio, and he even had his own cookbook. The 11-page booklet was packed with the greatest potato-centric recipes7. It fit very well into the historical context and proves to be an excellent source of information on the governments’ famine-prevention tactics.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

One such tactic involved using every last gram of the potato in the most ingenious ways. This is the common thread throughout the book. Advice ranges from always boiling the potato in its skin, to never throwing away the cooking water, which can become a delicious base for all sorts of soups. The booklet also reflects on the food shortage: “Incidentally, potatoes help to save both fat and flour in pastries, puddings, scones and cakes.” The scarcity of flour and certain fats becomes clear further on in the book: butter is not mentioned once. Margarine is used some times, and the rest uses ‘cooking fat’. Flour is used in only a few recipes, and only if strictly necessary. Small amounts of milk are part of some recipes, but only ‘if possible’.

It also displayed the strategy and concerns of the British government. Words such as ‘ration’ and ‘energy’ recur often. It is clear that the goal of the book was to promote healthier eating and to assist people in rationing. The potato was seen as a great tool to accomplish this: “And in the absence of fruit for the winter months, it supplies the valuable vitamin C.” The mention of the winter months suggests that the extensive use of the potato was not temporary; Pete was here to stay!

The fact that a small cookbook dedicated to the potato was published is in and of itself evidence for the apparent need to adopt the potato as an important daily food. It was of utmost use to uphold morale, create unity and solidarity: “Attack with me, says Potato Pete!”, or “I keep ‘em going, says Potato Pete!”, sitting on a battle-tank8. Eating potatoes was, thus, a weapon that everybody could draw, and a way of supporting those on the front-lines.

“It also displayed the strategy and concerns of the British government. Words such as ‘ration’ and ‘energy’ recur often. It is clear that the goal of the book was to promote healthier eating and to assist people in rationing.”

The first page shows a happily surprised woman, looking at Pete in awe. Sentences such as “Follow me, madam, I’ll show you a thing or two”, can be found throughout the book. Clearly, women were the ones in charge of preparing the meal. In this way, Pete also reflects aspects of the social structure at the time.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

The use of short and simple songs exemplifies that the booklet was made for a wide audience. The songs made it easy for everyone to understand, and one contains a direct reference to a very specific situation:

‘Potatoes new. Potatoes old

Potato (in a salad) cold…

Enjoy them all including chips

Remembering spuds don’t come in ships.’9

The final sentence of the rhyme sketches the handiness of consuming potatoes at that particular time. These wonderful ‘spuds’ did not come in ships, making them a great crop to cope with the shortages as a result of the Battle of the Atlantic. As the Germans did everything they could to establish a naval blockade, overseas supply of food to Britain was drastically affected. Potatoes, however, could be easily grown all across the country.

Potato Pete’s booklet has had a very obvious purpose and was not meant to be a timeless written work of cookery. Even if no context is given, it is evident that the booklet was made at a particular time, and with a particular purpose. However, this does not mean that Pete is a has-been. Due to the simplicity of the recipes, and the spud’s ever-lasting popularity, he became timeless after all. Perhaps, Potato Pete can still provide light in days most dark for those who need it.

Footnotes:

[1] “The Legend of the Potato King.” The New York Times. Accessed April 22, 2020.

[2] Joel Mokyr. “Great Famine.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed April 23, 2020.

[4] “Operations, The Battle of the Atlantic.” Canadian War Museum. Accessed April 23, 2020.

[5] “Dig for Victory.” British Library. Accessed April 22, 2020

[7] “The Potato Pete Recipe Book.” King’s College London. Accessed April 22, 2020.

[8] “Attack with me says Potato Pete.” Australian War Memorial. Accessed April 24, 2020.

[9] “Potato Pete.” The Home Front Housewife. Accessed April 23, 2020.

Photo Source: artsandculture.google.com

The opinions expressed in the articles of this magazine do not necessarily represent the views of

The New Gastronome and The University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo.