The New Gastronome

Nems Cook or Yam Naem?

A Madeleine de Proust Moment

by Candice Chemel

by Candice Chemel

On a warm, spring night in Mulhouse (Alsace, France), we walked a few blocks from home to have dinner at a thaï restaurant I had lacked to try before, Khrua Thaï. When looking at the menu, my dinner companion pushed me to order this starter, Nems Cook. Knowing me well, he swore I would love it. The name sounded a bit suspicious and unfamiliar, but I went with the flow. The dish was served, I took a bite, and my eyes directly swelled with tears. I knew exactly what it was.

In 2019, I was living in Bangkok. Right down the street from where I was living, on an unknown schedule, was this street vendor making this dish. She was often there late at night, and when I would come home and see her, I would go to her directly. She had only one item on the menu, and I was obsessed with it. I had no clue what it was called, or maybe she told me, and I didn’t understand it phonetically; I wasn’t sure what it was either. So I was instantly back there, standing in the hot and damp, buzzing city, waiting for this delish and making sure I was asking for it P̄hĕd (which means spicy) and not Pĕd (which means duck) because that just wouldn’t have made sense.

I knew it was moo (pork), but the specificities were blurry, and I didn’t mind; I didn’t really care. I don’t remember exactly the first time I ordered it. I was just on a constant crawl of trying every street vendor in my neighborhood, and my feet happily brought me to her stand. She didn’t even ask me really what I wanted and just made it. In a mixing bowl, she would first pour a little nuoc mam (fish sauce) and lime juice, add some shredded pork rind giving a bit of elasticity (it was actually this ingredient that I couldn’t really define), minced fermented pork for a bit of acidity, minced shallots, and then smash a fried rice ball in it. The balls are prepared beforehand. The mixing is done mostly by hand to not mash the preparation. Next, she would ask if I liked it spicy (duh) and add chili flakes and crunchy green chilies (P̄hĕd). She would pour everything into a plastic bag, top it with peanuts and give me another bag on the side with sometimes lettuce leaves or cabbage leaves and always piper lolot (wild pepper) leaves.

I would hold it preciously, get a Chang beer on the way and go back to my apartment. If I felt like being romantic, I would take it up to the roof, but most of the time, I would sit comfortably in my big armchair, pushed close to my balcony for a nice view but still sheltered from mosquitoes and in the AC. I would pull out a leaf and dive it into the other bag to shape it into a little ball, wrap the leaf around, and bite into it.

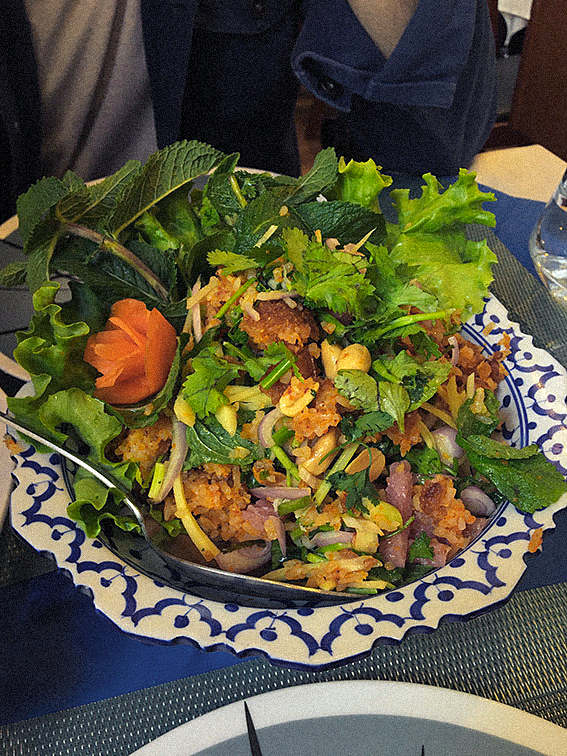

This is one of those dishes where every bite is the perfect bite. Maybe we even thought of calling it the perfect bite because of this dish. It is crunchy from the fried rice and the peanuts, spicy from the chilies, crisp and sour from the lime, deep and round from the fish sauce and meat, and fresh and slightly bitter from the leaf wrapping. A cold light beer on the side, and you’re on top of the world. This feeling would increase exponentially on the roof, of course.

This dish, for me, is particular to that time and place. It was not that I was seeking it out, but I never came across it anywhere else other than in Thailand. This intense revival of my flavor memory led me to dig a little deeper. As I had suspected, Nems cook is not the real name. It is called Nem Thadeua and originates from Laos, from the port village of Tha Deua, where starts Mittaphab bridge connects Vientiane in Laos to Nong Khai in the Northern East of Thailand. In the 60s, street vendors would cross the Mekong from Nong Khai to sell their specialty, nem (meaning fermented pork meat) in Thadeua. The dish spread in the Northern East and in the rest of Thailand when the Laotian migrated to Bangkok to work. It is actually known through a couple of names. Nam Khao or Nam Tod in Laotian, or Yam Naem Khao Tot or Neam Khluk (cook… khluk… I’ll give them that) in Thai. Khao means rice.

The Laotian usually cook the rice the day before, in a rice cooker, without adding too much water to have drier, stickier rice without too much starch. The rice is then assembled in balls with onion, egg, shredded coconut, coconut powder, salt, and paprika. It is advised to flatten the rice balls to have a more crispy surface. They are then fried and crumbled. The fermented pork is crumbled as well. It is called som moo (sour pork), a fermented garlic pork sausage mixed with thin strips of slightly elastic pork rind, a specialty from Luang Prabang. The seasoning is then rectified with chives, lime, nuoc mam, coriander, or mint. Some families add minced shallots, toasted peanuts, or puffed rice to add some more crunch. Each bite is wrapped in Batavia leaves, shiso, or piper lolot.

— side note — Coming from the Middle East, the tradition of wrapping meat in vine leaves has then been introduced to South East Asia. As the vines were not so happy in the south-east Asian climate, the Vietnamese substituted them with piper lolot, wild pepper that grows like weeds in the humid forest —

A. D. V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

At that restaurant in Mulhouse, they served it a bit differently. The leaves were placed on the plate with the rice mixture on top, making it less evident that it was a wrappable dish. I went for it with my hands anyway. Another thing was different; here I was sharing that dish. It somehow changes the soul of the dish to engage in it with someone else, even more, when it is from the same plate. One part of me was trying to make sure I would still get a fair share of those perfect bites; another part felt like I was transferring my emotions through the food and to my dish roommate. I could not stop talking about it. I felt like a grandma that you enjoy hearing the stories from but sometimes regret asking for them, not that anyone asked me here.

Thinking so much about it made me crave the dish again, and I decided to pick one up to accompany my writing. When I ate it at the restaurant, as that first bite made me travel back to Bangkok in the blink of an eye, I actually tasted what I was tasting there. I was not in the present anymore. I was tasting that special memory. Having it again tonight, the hype has faded slightly; it allowed me to look at their version and realize it was different on many points. The sausage was julienned instead of crumbled, I could not find the rind strips anymore, and I should have asked for more spiciness. However, tonight I was having it alone again, sitting on the carpet, the light rain patter on my window, wrapping precociously. One thing did stay the same.

In either situation or location, it made me feel at home.

Recipe

Yam Naem

Ingredients

For the rice balls (for 10-15 balls) (as it takes quite a bit of work, you could easily make a bigger batch and freeze the remaining rice balls)

– 300gr of Jasmin rice

– 1 onion (minced)

– 30gr of grated coconut

– 15gr of coconut powder

– 2 teaspoons of salt

– 2 teaspoons of paprika

– 1 small egg

– frying oil (and vessel)

For the salad (for 4 people)

– 10-15 crispy rice balls

– 200gr of som mou (in Lao) or nem Chua (in Vietnamese)

– fresh cilantro

– fresh mint

– chives (or spring onion, or thaï chives)

– lemon juice (or lime juice)

– 3-4 tablespoons of nuoc mam

optional: minced shallots, crunchy peanuts, chilies

for serving: Batavia, shiso, and piper lolot leaves

Cooking the rice (ideally the day before)

Rinse the rice with cold water and let it cook in the rice cooker, making sure you add less water than usual. The less starchy the rice is, the crunchiest and crumbliest it will get afterward. Once the rice is cooked, move it around gently with a spatula to let the remaining humidity out and let it cool down.

If you don’t have a rice cooker, rinse and drain your rice. Then, add it to a pot along with one and half times its volume of water. Bring it to a boil with a lid on. Once it starts boiling, open the cover slightly and let simmer for 15 minutes for the rice to absorb all of the water.

Forming the balls

Mix the rice with the minced onion, egg, coconuts, salt, and paprika. Form them into balls once it becomes homogeneous and flattens them a bit. They will cook faster and have a larger crispy surface. Ensure that you keep your hands wet to avoid the rice sticking too much to your fingers. Fry them in hot oil until they are crisp and golden. Let them cool down on paper towels to soak up the excess fat.

Building the salad

Crumble the som mou with your fingers. Pour some lemon juice and nuoc mam on top and mix well. Crumble up about 10 crispy rice balls and mix again. Rectify the seasoning with some more lemon and nuoc mam to your taste. Add chopped chives and fresh cilantro and mix one more time. Sprinkle some fresh mint leaves on top, and you are good to go!

The remaining balls can be frozen. Then, to use them again, let them defrost and heat them up in the oven to crisp up again before cooling down.

Photos ©Candice Chemel