The New Gastronome

Koji, Please!

Koji in Vegan and Vegetarian Diets

by Elad Liam

by Elad Liam

Let’s say I could give you something that would significantly and effortlessly elevate your food. Would you believe me? Let me introduce you to koji!

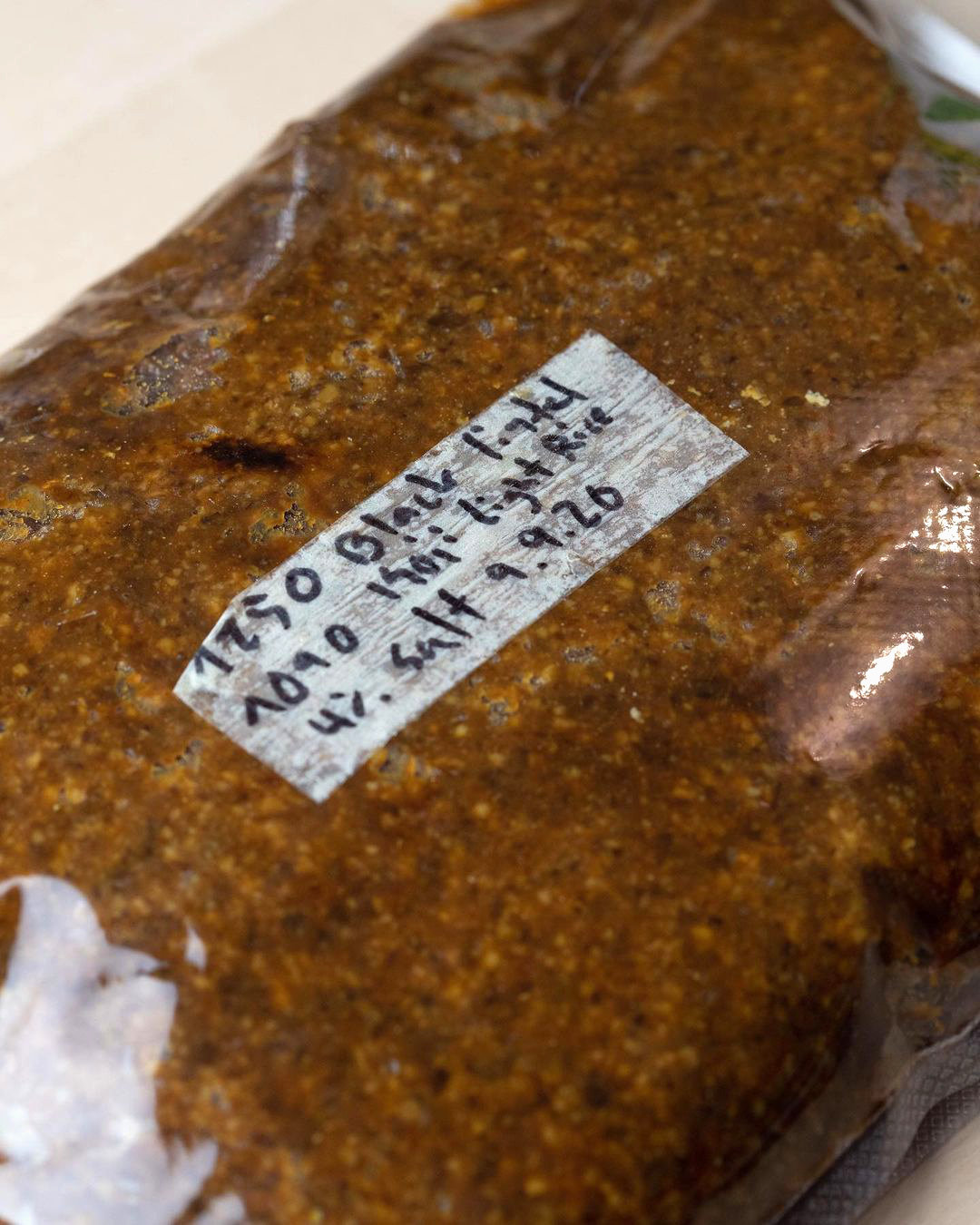

I hadn’t dealt with fermentation of any kind before my first year at UNISG, but once I met fellow students Matthes Harmms and Felina Graetz, we started talking about koji and concluded that it would be awesome to produce our own miso. Both professional chefs and vegan, Matthes and Felina were intrigued by fermentation and are now using at least one fermented element in each of their dishes. We also met with Shalom, an alumnus who had ventured down the path of koji production before, to ask him some questions and start learning more about the process. At that time, we could have never imagined what this little experiment would lead to: two apartments full of ferments, dealing with koji daily, with about 16 wooden barrels ranging from 10 to 50L, each filled to the brim, and even more vessels for smaller 5L batches of miso and shoyu.

So, what is koji? Koji is a mould. I know what you are thinking: that doesn’t sound very nice to eat. But, think about it. You wouldn’t mind eating blue cheese or wonder about the mould on aged meat. So, why be bothered by koji in your soy sauce or miso?

When we say koji, we usually mean Aspergillus oryzae, the most commonly used mould, though you can also try A. luchuensis and A. sojae. A. flavus, on the other hand, is one of the moulds we should not be consuming, as it is toxic. But back to A. oryzae: It has different varieties, each of them suitable for other uses. One will, for example, work better for soy sauce, another for miso or amazake, and another still might be better adapted for different substrates such as rice, barley or soy.

A. D. V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G.

Aspergillus oryza is bought in powder form, otherwise known as spores, and sprinkled on the substrate where it grows after a specific procedure until it overtakes the rice and makes it into ‘rice koji’. You only need a tiny amount of koji spores to make more: think, 1g of A. oryzae for 5kg of substrate.

“When we say koji, we usually mean Aspergillus oryzae, the most commonly used mould, though you can also try A. luchuensis and A. sojae.”

Remember how I told you that koji could make your food better? That’s because it is a wonderful source of umami. Umami is one of the five basic tastes, alongside salty, sour, sweet and bitter. It is quite new to this category as it was a recent discovery. The word umami is directly derived from the Japanese word meaning ‘delicious’ that usually describes savoury tastes. When we think of umami, we typically think of Monosodium glutamate (MSG), but in koji-related products, we are talking about amino acids. Technically, amino acids can be found in many different foods such as tomatoes, peas, asparagus and others we don’t usually associate with umaminess. Koji, however, has a trick up its sleeve: Its primary function is to break down the substrate and free the amino acids, making them taste a lot better or more umami. In a bowl of rice, the koji would help release the sweet compounds, making it taste sweeter than any rice without koji.

So, koji brings umami to food, but why should we want or need that?

Umami has properties that stimulate the mouth. By itself, it is not palpable, but mixed as one of many ingredients, it will create something delicious. The benefits of umami vary, but it’s been shown in many studies that especially the elderly benefit significantly from it. As their taste and smell sensitivity decreases with age, they are often no longer stimulated by food, which might cause malnutrition. When stimulated with umami, the mouth salivates more and sensitivity increases, therefore stimulating appetite and hunger.

Think about removing salt from all your meals. It would definitely detract a lot from them – the same is true for umami. Take meat and fish, for example: When the umami flavour hits our mouth, it gives us a signal to prepare to digest proteins, which triggers saliva and digestive juices to facilitate a smooth integration. Now, this is slightly different when it comes to vegetables, but the concept remains. Picking in koji products such as ‘koji-nuke’ (general picking bed from miso or shoyu solids) or Shio koji is fantastic to soften vegetables and give them a distinctive taste and texture.

Koji products include but are not limited to Soy sauce (usually called amino sauce, since it can be made of other legumes as well), miso (or amino paste, when not made from soy), garum (originally Greek fish paste, but can be made from other things), shio koji (or salt koji, an excellent marination mixture), and amazake (sweet and sour rice drink).

Strangely enough, umami can be quantified to a degree. We know soy sauce has amino acids, and we also know that all amino acids have nitrogen. Thus, if we measure the nitrogen quantity in soy sauce, we will have an understanding of how much amino acids – and, therefore, umami – it contains. This should get us an approximate result of 1.6g/100mL of total nitrogen, or 2.2g/100mL if we check a ‘tamari’ type soy sauce.

“The benefits of umami vary, but it’s been shown in many studies that especially the elderly benefit significantly from it.”

Of course, flavour is a bit more complex than simple numbers, and more umami doesn’t necessarily mean more flavour or better flavour. We need to consider many other compounds that affect one another when thinking of the end result… but it’s still cool to be able to determine how much umami you have in 100mL of soy sauce.

When we think of koji, especially when choosing what strains to use, we think of its enzymes – specifically amylase, protease and lipase. Those three enzymes are the source of koji’s awesomeness. When thinking about umami, we need to look at protease, which breaks down proteins into amino acids, like glutamic acid. Glutamic acid and a combination of L-glutamate and sodium chloride create MSG, otherwise known as umami itself. It is possible to buy MSG in powder form, which many eastern cuisines are known to use, but it will not be the same experience as using koji products with their added benefits of complexity in flavour and texture.

Though they cannot be seen by the naked eye and are often skipped over, when you dive into the details of koji, you can observe complex chain reactions as well as other simultaneous reactions. I first noticed it when I pulled a fully detailed diagram of the content of soy sauce from several pieces of research about its activity. We look at it closely; we can see that both alcoholic fermentation and acetic acid fermentation are happening. All these compounds make up the flavour and aroma of soy sauce, alcohol next to acids next to aldehydes next to polyols, esters, ketones, and so on. Many essential microorganisms cause these reactions, including fungi like A. oryzae, bacteria like Tetragenococcus halophilus and T. versatilis, as well as yeast like Zygosaccharomyces rouxii and more. This formation of alcohol, vinegar and other compounds can happen either simultaneously or in stages.

But, this fascinating fermentation process is only one of the reasons why I highly recommend getting to know miso and other koji products from artisanal or traditional places rather than from supermarkets. Artisanal miso tends to be more versatile and unique in flavour and easier to incorporate into a dish than the store-bought, mass-produced kind that often suffers from one-dimensional standardised umami taste and gets created in just a few weeks. This is not to say that it is bad. Still, it could be better.

“Even with high umami foods like tomato, peas or mushrooms, we don’t have the same effect as with koji. It’s just harder to get umami from regular vegetables.”

Let’s talk about umami in a vegan or vegetarian diet for a second. We have spoken about how meat products laden with proteins can quickly bring the umami factor and its benefits to food. But as a vegetarian with many vegan friends, I find it extremely interesting to see how miso performs doing that same job. The answer is, really, really well! So much so that I’m now actively missing it if it isn’t there. Again, think of not having salt in your food, and you’ll soon understand what I mean.

As mentioned before, umami is essential but not easy to come by in meat-free diets. Even with high umami foods like tomato, peas or mushrooms, we don’t have the same effect as with koji. It’s just harder to get umami from regular vegetables. If you have ever tried to make vegetable broth before, you will know that getting something as umami as meat or bone broth is hard. For both vegetarian and vegan diets, you will need a good source of umami like dried mushrooms or seaweed, but even then, you might need more umami – mainly to reach a certain level of complexity. At the same time, umami is easily obtained from koji products like amino paste and amino sauces that can be incorporated into any dish: problem solved!

Currently, I’m experimenting and pushing the boundaries for even more opportunities to incorporate koji. A fellow student and I made a koji paste to fill some croissants, for example. It definitely needs more work, but I just loved the idea. Next on my list is growing koji directly on vegetables, something I’ve wanted to do for a long time and now finally have the time to start.

Whether you are vegan, vegetarian or eat everything, I think you should definitely try koji products in your kitchen and experiment yourself. Start from simple miso soup, and go towards marination with Shio koji or add a bit of complexity with a teaspoon of miso or shoyu to your everyday cooking.

It is hard to pick just one recipe, but I think this one is a good and easy dip into the world of koji. A glaze that you can put on anything for extra flavour and complexity. I like to cut vegetables in half and then crave criss-cross grooves in them for the glaze to penetrate. Feel free to experiment with it.

Miso Glaze

Technically, this is a glaze, but you can also use it as a marinade with Shio koji. Here, you will mainly want to look for the flavour and complexity.

Note: Don’t forget that miso and shoyu contain a high amount of salt. Store-bought miso and shoyu can contain about 20%, sometimes even more, while artisanal ones tend to have 4% in miso and 12% in shoyu.

The opinions expressed in the articles of this magazine do not necessarily represent the views of

The New Gastronome and The University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo.

Photos ©Elad Liam