The New Gastronome

Omakase

Savouring the Irretrievable Moment

by Math Mönnich

by Math Mönnich

It was a grey, rainy and seemingly endless afternoon on a late fall day in Germany. Trying to counterbalance the leaden weight the weather gods had imparted, I was looking for something that would lift my spirit and give some comfort. I found it in the form of an audiobook by Trevor Corson called: The Story of Sushi.

The book follows a young female protagonist, while she pursues an apprenticeship in a famous Californian Sushi school. As her development unfolds with all its detours, a summarised history of Sushi in its country of origin, Japan, is given as well. It is a diverting, well-narrated story. Besides having the desired effect of taking me to other parts of the world that seemed more alluring, I also had my first encounter with Omakase, a distinctive way of ordering food in a Sushi restaurant.

Like so many things in Japan, a seemingly simple word as Omakase contains a whole world in itself. “I leave it up to you” is one commonly acknowledged way of describing its meaning. Rather than ordering á la carte, the inclined customer leaves the selection of dishes up to the chef and therefore does not know beforehand what he is about to be served. But that’s still too simple. “I’m putting my culinary faith into your skilful hands and trust your judgement of choosing the best ingredients according to their intrinsic quality, prime state and their ideal combination for carving out the utmost delectability”, would be a more accurate description. Apparently Omakase derives its meaning from the term Makase Ru which translates to: “I confide in you” or “I surrender my will.”

Surrender your will and ponder the implications of such a concept for a moment. Instead of a menu that changes according to the seasons, this menu changes every few hours or couple of days, depending on the chef’s foray into the market. During his shopping spree, he forms the menu around the availability of products at their prime. Along with the gustatory bonus, this gives a conservative one as well. Instead of buying produce for a predetermined menu offering plenty of options to the guests and causing excess, only ingredients for one menu are bought.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

My first real-life encounter with this concept happened in a Berlin-based Japanese restaurant, called Shiori, which is entirely dedicated to Omakase.

It is a rather small restaurant that seats ten people with a minimalistic, yet appealing interior. Shiori is lending the guests enough comfort without any distraction from the real show, the food. The one seating per night needs to be booked ahead and is being served at 7.30 PM sharp. Guests are encouraged to arrive 10 minutes prior, making sure they are on time and comfortably settled in by the time the first dish arrives.

“I’m putting my culinary faith into your skilful hands and trust your judgement of choosing the best ingredients according to their intrinsic quality, prime state and their ideal combination for carving out the utmost delectability”

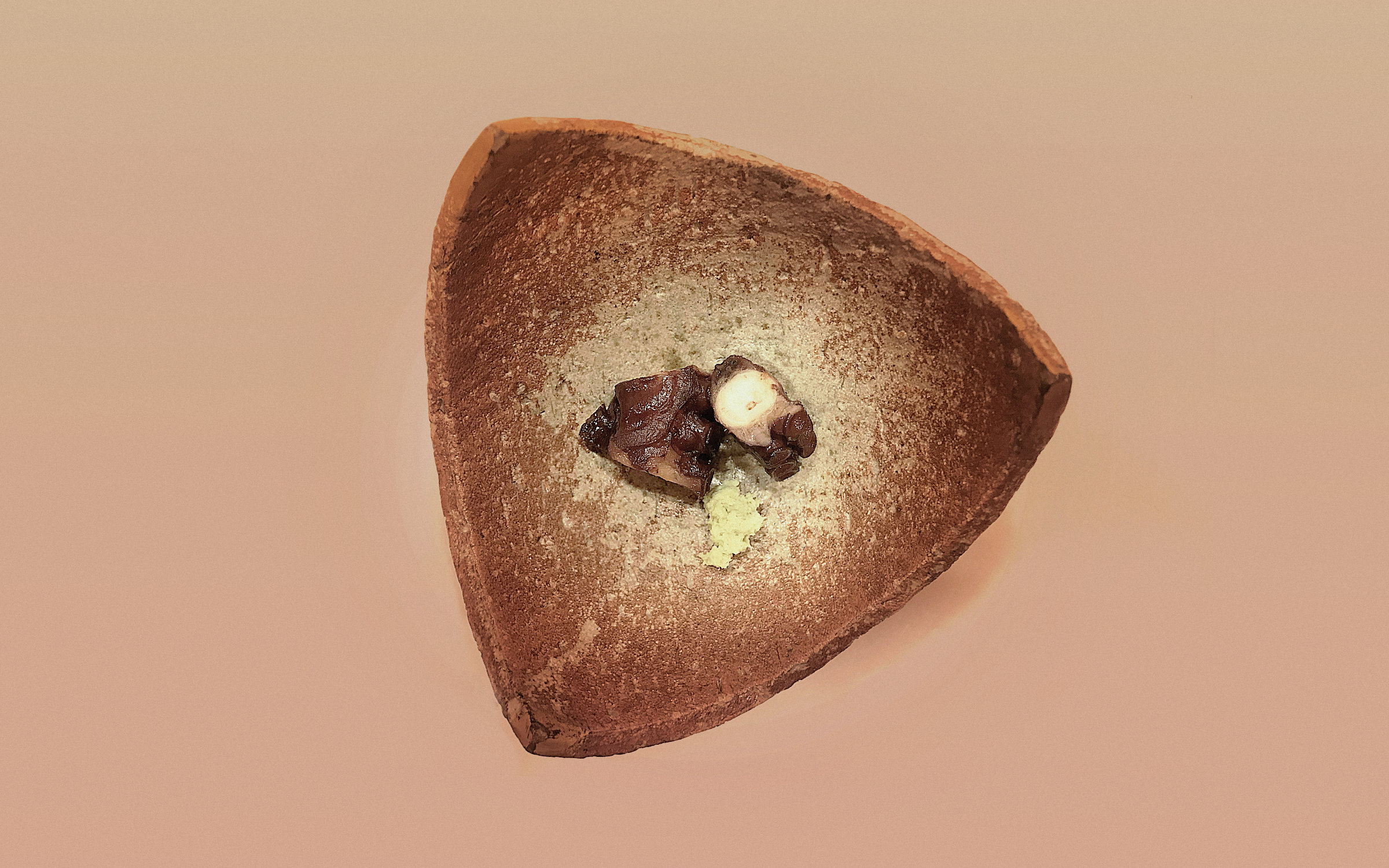

And, with the accuracy of a Swiss watch, the first dish is, indeed, served at half-past seven. Consequently, there is no time wasted between courses. The intermissions are just long enough to quickly recap what I just ate and to ponder how it affected my most intimate senses without being carried away by committed conversations. Again, the food demands the primary focus. The young chef singlehandedly prepares every single one of the eight courses himself and presents them on plates that are quite often uniquely handmade themselves. Every segmented dish is a reflection of the Japanese fondness for colour, taste and texture combinations, which results in rather complex courses.

The chef composes and serves the meals with little help from culinary gadgetry and only a kitchen hand for serving and clearing the dishes. He is in plain view for us at all times, as we sit around the counter. His movements are swift and precise, his polite demeanour allowing for questions without being a chatterbox – an Alfred Pennyworth-esque behaviour, if you like.

It is a delightful introduction to this particular way of eating and, most fortunately, it wasn’t my last opportunity. The culinary gods still had something up their sleeves and allowed me to partake in an Omakase experience of another level in its country of origin.

Unlike Germany, Japan is entirely surrounded by water and over the centuries people have learned to put the bountiful offerings of the maritime flora and fauna to use. Food from the sea is deeply entrenched in Japanese culinary culture. Therefore, it didn’t come as a big surprise that just two out of 23 courses were based on produce coming off the land while the rest was comprised of seafood, at my first truly Japanese Omakase in Tsugu Sushimasa, Tokyo. Again, we decided to sit at the counter even though there were little niches that allowed for privacy while eating. But we didn’t come for privacy, we came to witness the skilful craft of a Sushi Master that is best observed by sitting in the front row.

This time the chef of the restaurant is a bit more extroverted than the one at Shiori. With a loud and clear voice, he commands what needs to happen in the kitchen, which is out of view, to assist in the creation of his next course or to refill our glasses. Every time he commands in his military fashion, someone in the kitchen is replying in an affirming manner. Regardless of the aiding assistance of the kitchen team, the chef singlehandedly assembles the courses in plain view and is handling the key components of every dish alone, while conversing about food with us and thus investigating eloquently if we may have any restrictions on what we are willing to eat. After discovering that our curiosity doesn’t allow for constrictions, he starts boldly with a sea snail in its own shell, accompanied by a small cup of raw glass eel and brined hair algae. How did it taste? Close your eyes and recall your last trip to the sea and the peculiar smell of it. Now transform that smell into taste and you basically get what we just ate – the essence of the ocean.

“But we didn’t come for privacy, we came to witness the skilful craft of a Sushi Master that is best observed by sitting in the front row.”

Forgive me for not filling you in on the particulars of the following dishes. As you can imagine, their descriptions would fill the entire magazine. But I won’t deprive you of the dessert which is a reflection of Japanese culture, not for what it is, but rather for how it has been made. A single tomato. Grown in saline soil, the plant, in its survival mode, put all its efforts and goodness into its fruits resulting in the fruitiest and juiciest tomato I have ever eaten. Of course, I did not have to worry about the tomato skin, as it had been taken off by the chef, using his knife.

I am deeply grateful for these two opportunities, fulfilling my desire to be carried away by a comforting Omakase experience. While both occasions were highly enjoyable, they had two entirely different characters, spotlighting different aspects of Japanese traditions. At Shiori in Berlin, the number of courses accumulated to a third of those at Tsugu Sushimasa and, therefore, were presented with a higher complexity due to the number of ingredients used in a single dish. An opulence of flavours was the unavoidable outcome, like the staccato at the end of a firework, demanding a very sharp concentration for the inclined and willing eater in his quest to single out the particulars.

In comparison, the food at Tsugu Sushimasa was a different kind of ballgame. An extensive succession of puristic, handcrafted dishes, whose alterations were barely noticeable, composed by the chef aiming to carve out the intrinsic qualities of the produce he had selected just a few hours earlier. Simplicity is an art in itself and the chef at the Tsugu Sushimasa demonstrated this art in a masterly fashion.

Both occasions were a reminder of the singularity of every passing moment and the beauty that arises from surrendering one’s will to a masterful mind.

Itadakimasu!