The New Gastronome

Grape Forward

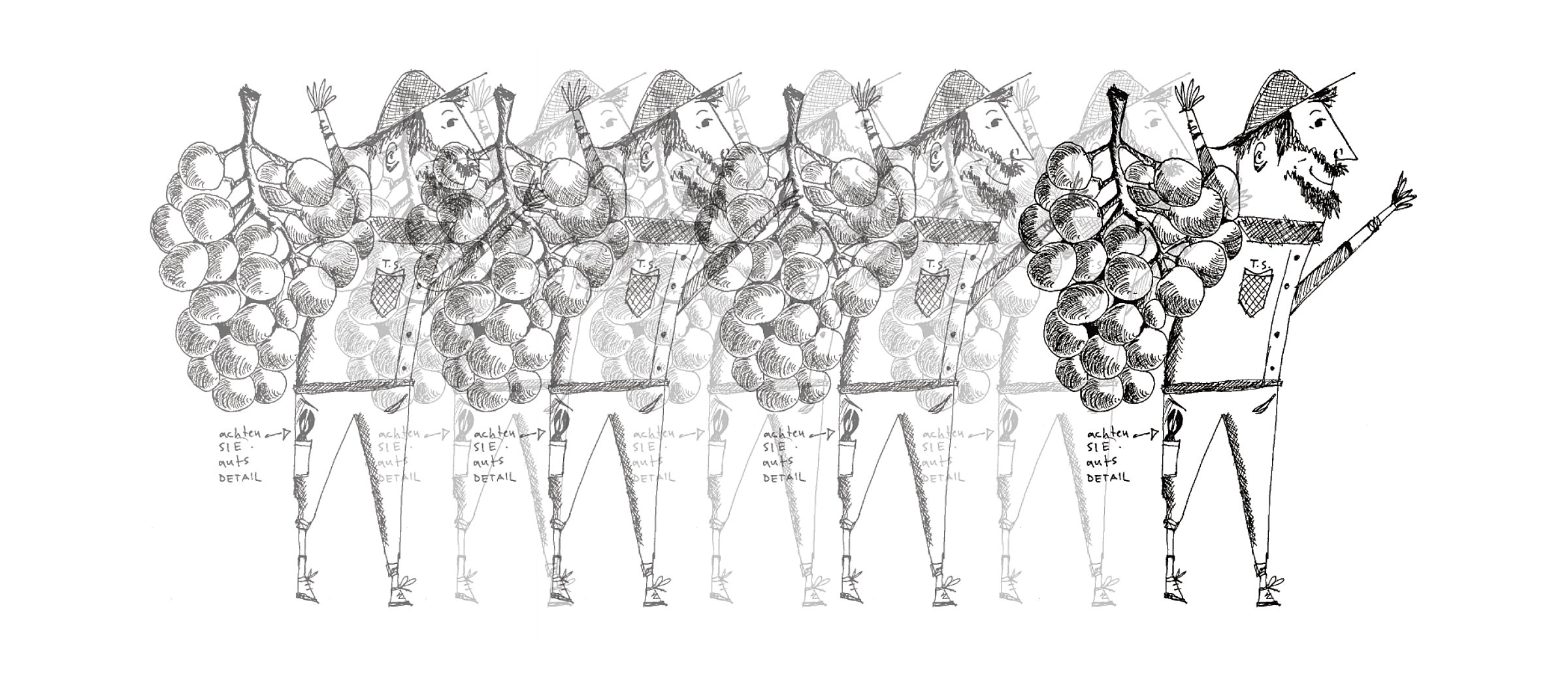

The Swiss Who Grows Grapes For a Living

by Nancy Monperousse, This Schälchli

by Nancy Monperousse, This Schälchli

Switzerland is synonymous with fine chocolates and luxury watches, but, when most people think of wine, other countries usually come to mind. However, wine has been a part of Swiss culture for centuries and while it doesn’t have a reputation for being of high quality, there are a growing number of Swiss winemakers who are working to dispel this notion.

We sat down with 33-year-old Swiss winemaker and University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo alumni, This Schälchli, to learn more about how he got his start in winemaking and to get an in-depth look at the winemaking process and wine culture that’s taking place, in Switzerland.

Why Wine?

I graduated two years ago from a viticulture and winemaking apprenticeship and I remained with both vineyard work and winemaking. I got into wine because of my upbringing and surroundings, and my experience at the university. I grew up in Zurich, close to vineyards. The city of Zurich even has three different wineries and more than six hectares of vineyards. So, when I was a teenager, during autumn vacation, I would start picking grapes at harvest. Then, while I was a student at the university, I worked at the Banco del Vino throughout the three years of my undergraduate program. Initially, I was more interested in natural sciences, but as I got more interested in the production and transformation of foods and beverages, my interests started to change. My only 30 [perfect score/grade] was in viticulture, which was taught by Professor Franco Mannini. I enjoyed the course a lot. It was probably him, and Professor Nicola Perullo, with his philosophy of taste, where wine was a big subject as well, that really triggered my interests in wine. These were all puzzle pieces – then it all came together and became winemaking.

Apprenticeship: The Road to Swiss Winemaking

In Switzerland, to become a winemaker (vintner/grape producer), you have to complete a three-year apprenticeship. Of course, you can make wine without this apprenticeship, but the apprenticeship is a good education to have and the diploma is legally accepted. After graduating from UNISG in 2015, I read about this winery – Cicero in Graubünden – and one morning, I called them to see if they would accept me as an apprentice; and, it just so happened that they needed help. They told me that they were looking for someone and they asked me to stop by. The next day, I went; it became an immediate friendship and I stayed.

A. D. V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G.

During the three year apprenticeship, you have 12 weeks of school, per year, in blocks of four: for three weeks, you go to school; then for three months, you work in the vineyards and in the cellar; then you go back to school and so on. Repeating this process, for three years, gives you a great chance to learn theory and practice (and responsibility) – driving tractors, pruning, pumping wine, bottling, et cetera. It’s a great dual system.

Because every winery has different grape varieties, soil types and climates, and might have different approaches to farming and winemaking (conventional, organic, bio-dynamic), it’s recommended that you change wineries after every year of apprenticeship. I changed once, too. I completed my first year of apprenticeship at Cicero Weinbau, in Graubünden, and finished my apprenticeship at Weingut Eichholz, in Bündner Herrschaft. After my apprenticeship, I looked for a winery that was closer to home (Zurich) and had a sustainable approach to winemaking. I knew this guy, Tom Litwan, and he’s considered to be one of the most interesting winemakers; he’s young, he’s fun, and his winery is Demeter certified. And that’s where I am now. It’s been a little more than a year and Tom is a great person to work for.

The Winemaking Process

From January to the end of September, maybe the beginning of October, we’re in the vineyards, producing grapes. The whole process, from the time that we start harvesting to the time the still wines hit the bottle, more or less, takes one and a half years. We work with four grape varieties, mainly Pinot Noir. It might not be considered a Swiss grape variety, but, it has been grown in Switzerland for way more than a hundred years and, according to a few encyclopedias, if it’s been grown here for more than a hundred years, you can call it autochthonous. Then, we do Chardonnay, more out of love to the grape, and it grows very well in our wine region Argovia (Aargau). Then, we have Riesling-Sylvaner aka Müller-Thurgau and Petit Méslier, a champagne variety, because we also produce a really good sparkling wine. We also do ciders (sour cherry, apple and quince).

Pruning Systems

The work of pruning is so important because it can really affect the health of a vine. It’s the first step of yield control and if you prune cleanly, you might have less work during the summer. With a healthy or a smart pruning system, you can prolong the life of the vines and you will have a more regular leaf canopy. The vine training systems we use are Guyot, double Guyot and Lyra. Of all vineyard work, I love pruning the most – more than any other work done in the vineyard. It takes a lot of practice and thoughtfulness. Pruning time, in winter, is also my favorite time of the year because it’s relatively quiet. If you have 80 hectares to prune, you might be under pressure, but we basically just have five and a half hectares. It’s cold, of course, but as long as you have some tea and you move, you’re fine.

The wonderful thing about vineyard work and winemaking is that it is so diverse; the work changes with the season and every vegetation phase. Conditions this year will be different from last year, and every vintage makes a new wine. And, you only have one chance per year to do it right. I always try to remember what I thought I did wrong last year and the next year, I want to do it better.

Most of the manual labor done in the vineyards might be simple. But, it takes a few years to understand the links between all the work you do in the vineyards. Everything is very connected – there’s always a chain reaction. You do something and it affects the next step; it all goes hand in hand. Again, the pruning probably takes the most practice. It’s challenging, but it’s wonderful. And the scissors – I don’t know – I just love this object.

During and after the harvest season (September to October), we start working in the cellar again, making wine: destemming the red grapes, whole cluster pressing the whites, fermenting, piegage, checking sugar levels, et cetera. But once the young wines hit the barrels, in winter, we literally don’t touch them for one whole year.

A Bit About Spontaneous Fermentation

We ferment everything spontaneously because we strongly believe in it. The wines become more interesting, more vibrant, and alive. In addition, as a Demeter certified winery, we are obliged to go without selected yeasts. Most of our red Pinots are fermented in wooden vats, while Chardonnay and the base wine for Bubble are fermented directly in old barriques. Only the Riesling-Sylvaner goes through fermentation in a stainless steel tank. During spontaneous fermentation, like with sourdough, there are many different microorganisms taking part in the whole process. With wine, you can really observe this process. While some wines might not move (start fermenting) for three weeks, others start immediately and grow funny, gelatinous textures or foams on the top surface that you don’t see if you use selected yeast. It’s not just what you see, but also what you smell; different bacteria and yeast cultures might go from a pear aroma, to quince, and to rhubarb pie, during this stage. But in the end, the good yeasts always takes over and ends the alcoholic fermentation.

In 2018, for the first time, we had some difficulties with some of the fermenting Pinot Noir vats. The vintage 2018 was very hot and dry. We had already begun harvesting in early September, with weather temperatures of 30°Celcius – conditions at which cooling grapes might be absolutely necessary. But, we didn’t have that infrastructure yet; meaning that making spontaneous fermentation with warm grapes could be quite a challenge because microorganisms started attacking the sugars before the grapes arrived at the winery. It resulted in some single vats, from 2018, being slightly higher in V.A. than the vintages before. But, it’s all still within a very acceptable range.

With most grape presses, you can choose a pre-set press program and let it do its thing. But out of necessity, we had to operate our press manually, where you decide by observing when to augment or reduce pressure and when to break up the pomace. It takes much more attention this way, but in fact, I learned a lot about the grape differences between parcels and varieties. Every grape variety, in every vineyard, has a different skin texture and pectin structure which I only learned about because I was forced to manually control the pneumatic press.

Wine Additives and Plant Protectants

The only additive we use during winemaking is sulfur, nothing else. For us, it’s like an insurance. We simply cannot afford to lose a big tank or even a barrel. There is some sulfur added into the must and a small quantity is added, before bottling, to protect the wine from oxygen.

We are Demeter certified and produce all the preparations ourselves, and I still have to learn a lot about it. It’s impossible to learn everything after working only one year for a biodynamic winery.

We’re still dependent on copper and sulfur to protect the vines, among other things, from Peronospora (downy mildew) and oidium (powdery mildew). But, we try to do as good of a preventative job, as possible, to use as little copper and sulfur in the vineyards, as possible.

Challenges to Growing Grapes

There are many things that affect all of our vineyards: the most harmful to us are hail which mostly occurs during summer, and late frost, which occurs early spring (mid/end April). We had considerable damage from late frost, in 2016 and 2017, two economically difficult years for everyone. But, the vine is a very sturdy plant and you will always harvest something and it may even be of great quality. For example, I love vintage 2016. It’s cool and it’s fresh! In 2018, we had several hails, which luckily only damaged two of our six vineyards. That’s why it’s good that we have our vineyards distributed in two valleys and six towns. And by the way, the Frick Valley, where we are, is gorgeous. It’s on the sub-alpine mountain range of the Jura mountains. You should visit!

Are Swiss Wines Well Known Around the World?

No, I guess not. Although there is a fantastic wine-drinking culture, in Switzerland, the in-depth knowledge and traditions in other countries are stronger. The price for a Swiss wine is higher than for the same quality foreign wine, and that’s simply because the Swiss Franc is so strong. Just about everything here is more expensive. The Swiss wines, until the 1980s and 1990s, which I haven’t tasted, weren’t of good quality – so they say, quantity was more the parameter. And I guess our image still suffers from those decades. But times have changed and new generations have learned to do things different or better. Today, I think Swiss wines – especially wines from high-quality winemakers – can easily keep up with foreign, more famous wine regions at the same price level and what is special about Swiss wines, I think, is you get more manual labor, more craft for fewer dollars than in other countries.

What Are The Characteristics of Quality Swiss Wines as Compared to Wine From Other Countries?

I would say two things: mostly, they are very delicate wines because we grow grapes on quite a high altitude and cooler climate; we’re on the north side of the Alps. Our vineyards, in Argovie, are 500 meters above sea level. Since it’s never so hot, we cannot make heavy or strong wines because we just don’t have the hours of sun, nor the heat. But hey, that’s great for me because I love fresh and delicate wines. And, what I think is very cool in Switzerland is, most often, the winemaker is also the grape producer. In all of the places I’ve worked so far, the boss and head winemaker (same person) has been in the vineyards as many hours as her/his employees.

What is the History of Winemaking and Wine Culture in Switzerland?

In Switzerland, there are about 15,000 hectares of vineyards. In comparison, Italy has 700,000 hectares. I don’t know how many grape producers or winemaker families there are, but most of the vineyards are passed down to the next generation, sooner or later. And most Swiss towns probably once had some grape vines planted. You can see that if you look at land registries, with old field names, and every town has a vineyard road or a restaurant called “Zur Traube” (translation: To the grape) or “Torkel” (translation: wine press). My experience working in restaurants and serving wines at wine fairs is that the average Swiss wine drinker has a good amount of wine knowledge. They know many different varieties and regions; they have travelled for wine, and speak a certain level of wine language. Compared to Italy, Portugal, Spain, or France, the average knowledge about vineyard work might not be as high here. But, what is kind of nice is the wine Switzerland produces is largely also drunk within the country. We more or less drink what we produce. That’s quite a sustainable marketing system, but sometimes, it feels like we lack a bit of the connection, the inspiring exchange to winemakers and mongers abroad.

Are There Any Issues in The Swiss Wine World That Are Barely Covered and Should Be Covered More?

For me, one is the glorification of wine and the prices such wines achieve. Always remember, a bottle of wine is just one kilogram of fruit. I’m not talking about the €30 or €60 bottle of wine. I mean the really expensive wines. It’s fine to me if people are willing to pay any price for a bottle. But just remember, it’s not rocket science, it’s one kilogram of fermented grapes. Of course, some areas need more labor hours than others. But if you break it down, making wine is simple, but you can always make it sound more complicated.

The other issue is that of subjectivity vs. objectivity. The more I learn in this business, the more I’m convinced that true objectivity doesn’t really exist. You drink wine, and your perception of that wine will always be subjective. There’s not much more to say, don’t you somehow agree?

In Your Opinion, Why Are People Not More Receptive to Swiss Wines?

Well, I guess it all comes with knowledge. You might know something about wine from the Loire Valley, and you start liking them. You know something about wine from Piedmont, and you learn to love them. But, you don’t know anything about wine from Switzerland, and, I’m sure you have talked about pleasure through knowledge before. If you don’t know anything about Swiss wines, how can you enjoy them?

We’re not straight A students when it comes to wine marketing and communication. I mean, chocolate, banks, and watches – yes. The thing with winemaking is, a lot of winemakers today started one or two generations ago as farmers. They made grapes, but they also had cows, crops, orchards; they didn’t study wine marketing. So now, the system is run by people who follow farming traditions from two generations ago and that’s nice, but, for communication, worldwide communication, and marketing, and trying to be sexy, we – as a country – have a long way to go. And because we sell most of our wines in Switzerland, there’s no need to market elsewhere, but, we are trying. Just wait for us, we’ll get there!

Are There a Large Number of Younger Swiss Wine Producers?

Working vineyards and making wine seems to be pretty popular right now. I know many people of all age groups that are studying viticulture and there’s a considerable amount of career changer winemakers, like me, who don’t have a family winery. And you’ll find many young Swiss winemakers studying and working abroad to bring home knowledge and experience. Although it is a nice job, it’s difficult. After all, everything sounds so romantic, but there’s a lot of financial pressure on many of us. And don’t forget, it’s a physically challenging job. I know many winemakers who cannot hold a pair of scissors for very long anymore, or suffer from considerable back pain. So far I’m lucky, I’m healthy, and I love my job. The good thing is, to me, it hasn’t felt like work, so far – not for one day, during the past five years.

What are Your Future Goals as a Winemaker?

I really love the taste of wine; it’s a very emotional matter to me. For some people, it’s cheese, for some people, it’s music. For me, it’s liquids. The flavors and life of liquids. Of course, I would like to make my own wine one day, but it’s not my biggest goal. I enjoy being employed. It’s more important to me to continue, to learn, and to be patient. Maybe one day I’ll make my own wine – maybe not. I’m happy now. I want to grow with the wine company I’m working for right now (Tom Litwan, Argovia). But, I don’t have a clear or thought out plan for the future. One never knows…maybe it’s better not to have a strict plan. My biggest goal, right now, is to continue having physical health so I can continue to do what I’m doing.

Illustration ©Vroni Von Manz