The New Gastronome

以 心 伝 心

An Obento Says More Than a Thousand Words

by Eleonora Badellino

by Eleonora Badellino

Though, probably the most well-known lunch box in the world today, the history of Japanese Obento saw its invention as a daily necessity, allowing farmers and shepherds to take their lunch with them during long working days away from home. Who could have thought that this simple item, would someday become a symbol of the country, able to fascinate children with its shapes and colours, and fill the stomachs and hearts of adults?

Obento as Kawaii Items

With its more than 3.2 million tags on Instagram (#bento), Japanese bento or Obento (the “o” indicates an honorary form) wins the prize for social popularity among the homemade box lunches made to be brought to work, to school or to an outdoor picnic. Creators of these small gastronomic wonders are usually mothers or girlfriends, who set their alarm clocks one hour early every morning, wear their aprons and assemble the boxes using the ingredients already cooked the night before.

From their beginning as simple lunch boxes with several departments, in which all the ingredients were well preserved (this was at around the 5th century), the bento has been characterized by big changes related to its box material, ingredients, way of consumption and many more.

At the beginning of the 90s, its moment of transition from functional use to キャラ弁 (kyaraben), the ultimate adorable (kawaii) Obento, took place. Rice balls were modelled and coloured in order to take the appearance of famous cartoon characters, fried eggs were prepared in the shape of the sun and stars, sheets of Nori seaweed were cut out to create letters of the alphabet (or better, hiragana, katakana, and Japanese kanji, all part of the Japanese writing system) and more. Daily TV shows, books, and famous blogs gave advise on how to prepare them in a functional and useful way, starting from the choice of the raw materials to their preservation. Chain stores, where nothing costs more than 100 Yen (less than 1 Euro), gave space to entire sections dedicated to accessories, for people to personalize their bento, always keeping the kawaii look that set them apart. Especially with kids, it was difficult not to include their favourite cartoon shape in a delicious meal. And really, who could be surprised, taking into account that Japan had always been a country where, in some aspect of daily life, fantasy coexisted with reality?

“In a country where instead of “direct talk” people prefer 以 心 伝 心 (ishin-denshin), a tacit understanding through non-verbal communication, it’s not surprising that this object became a means of support.”

But why pay so much attention to a meal that would quickly be consumed, perhaps without too much attention? The truth is that the preparation of the Obento is a real form of communication between the maker and the receiver. In a country where instead of “direct talk” people prefer 以 心 伝 心 (ishin-denshin), a tacit understanding through non-verbal communication, it’s not surprising that this object became a means of support. For wives or girlfriends, it turned into a way of expressing feelings of love and respect towards their partner and for mothers, it was a show of support for children during their school career.

A. D. V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G.

So why not customize them, inserting details that contain a personalised element to represent the relationship, while still being pleasing to the eye and the palate?

While Obento can be seen as a sign of the country’s pop culture, it is also a representative element of Japanese social and religious life.

Obento as a Traditional Moment of Pleasure

Before the introduction of cartoons into Obento, with sausages shaped like octopuses and vegetables carved to form flowers, Obento was (and still is) considered a lustful gastronomic moment to be consumed during an important social or religious event. Kabuki (traditional theatrical performances), spring hanami (the time where people enjoy the beauty of the blooming cherry blossoms in parks together) and other such events, would not be the same if they were not accompanied by homemade Obento.

The same is true for important moments during the year in which Japanese spend time with the whole family eating traditional food together, such as the New Year Celebration, where the Osechi ryouri is the protagonist.

Forget the small wooden or plastic boxes that are easy to carry with you in your bag. The Osechi ryouri is, in fact, the maximum expression (both in quantity and quality) of Japanese Obento. It is a lacquered wooden container, built on 2, 3 (or more) floors, filled with many small portions of traditional dishes in each level, all linking back to a specific meaning of good luck for the new year:

Kuromame (Black beans): Health

Kamaboko (Fish cake): Good Luck

Datemaki (Omelette mixed with mashed shrimp): School Commitment

Konbu (Variety of algae): Happiness and Personal Joy

Shrimp: Longevity

Satoimo: Maternity

Renkon: Future without Obstacles

Kurikinton (Sweet chestnut dumpling): Financial Prosperity

During the days before New Year’s Eve, the women of the house prepare the dishes in large quantities, so that they can enjoy the passage of the year without having to cook.

Obento as Local Treasure

Since I moved to Japan, one fun fact that I realized about Japanese people is that they love trains. I am not referring only to the innocent passion of kids. Also, adults can not wait to enjoy a journey around the country sitting on a high-speed line. I can understand why: cleanliness, order, punctuality, functionality are all characteristics that trains share here, but there is more. There is one thing that makes this way of travel a special pleasurable experience:駅弁, ekiben. In Japanese, the word is composed of 駅 (eki), which means “station” and 弁 (ben), which is an abbriviated dialect form of bento and includes all the Obento categories that are consumed while travelling by train in its meaning.

With the development of the first Japanese railway network, which connected the country from the North to the South, there was a need to offer meals to travellers who were about to make long journeys. At each station vendors started to appear, who sold ekiben (at that time called Onigiri) to travellers leaning out of the train windows. Soon itinerant stalls began to emerge in every station, which later turned into real shops where this kind of travel meal began to take shape with its own identity. All ekiben were different depending on the area of the country they were sold in, their use of local ingredients, customized packaging and sophisticated presentation: from kanimeshi (crab rice) to tottori (the plump oyster from Hokkaido), nigiri sushi from Nara and wagyu beef from Kobe, every ekiben started to express and represent the local food.

After the big success, campaigns were started all over the country to show travellers a gastronomic map of Obento. In the absence of the internet, a magazine was published, in which the ekiben available in the various stations of the different prefectures were listed. Even big cities started to indicate the local ekiben next to the time tables of their train stations. All of this happened at the beginning of the twentieth century.

“There is nothing more pleasant than travelling around the country, eating an ekiben prepared with the products of the land you are looking outside of your window, with its landscape and its colours.”

Around that time ekiben created a proper tradition that, in particular with the construction of the high-speed network, kept growing in popularity, thus surviving until now. Nowadays, at each shinkansen train stop, you can find large departments where you can buy or assemble them by choosing from the local products offered.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

Yet, the vision the Japanse have of ekiben goes much deeper than just a simple packed lunch for the journey: “There is nothing more pleasant than travelling around the country, eating an ekiben prepared with the products of the land you are looking outside of your window, with its landscape and its colours.” (Yosuke, 33, Yamagata Prefecture).

The Japanese Obento, whether in their form of a travel companion, social entertainment or pop-culture staple, is a gastronomic pleasure that goes beyond their appearance as a packed lunch. They are a symbol of the country’s gastronomic tradition, a way of communication and a representation of local food culture. A small treasure that reminds us to keep our eyes open to the gastronomic wonderland that is Japan.

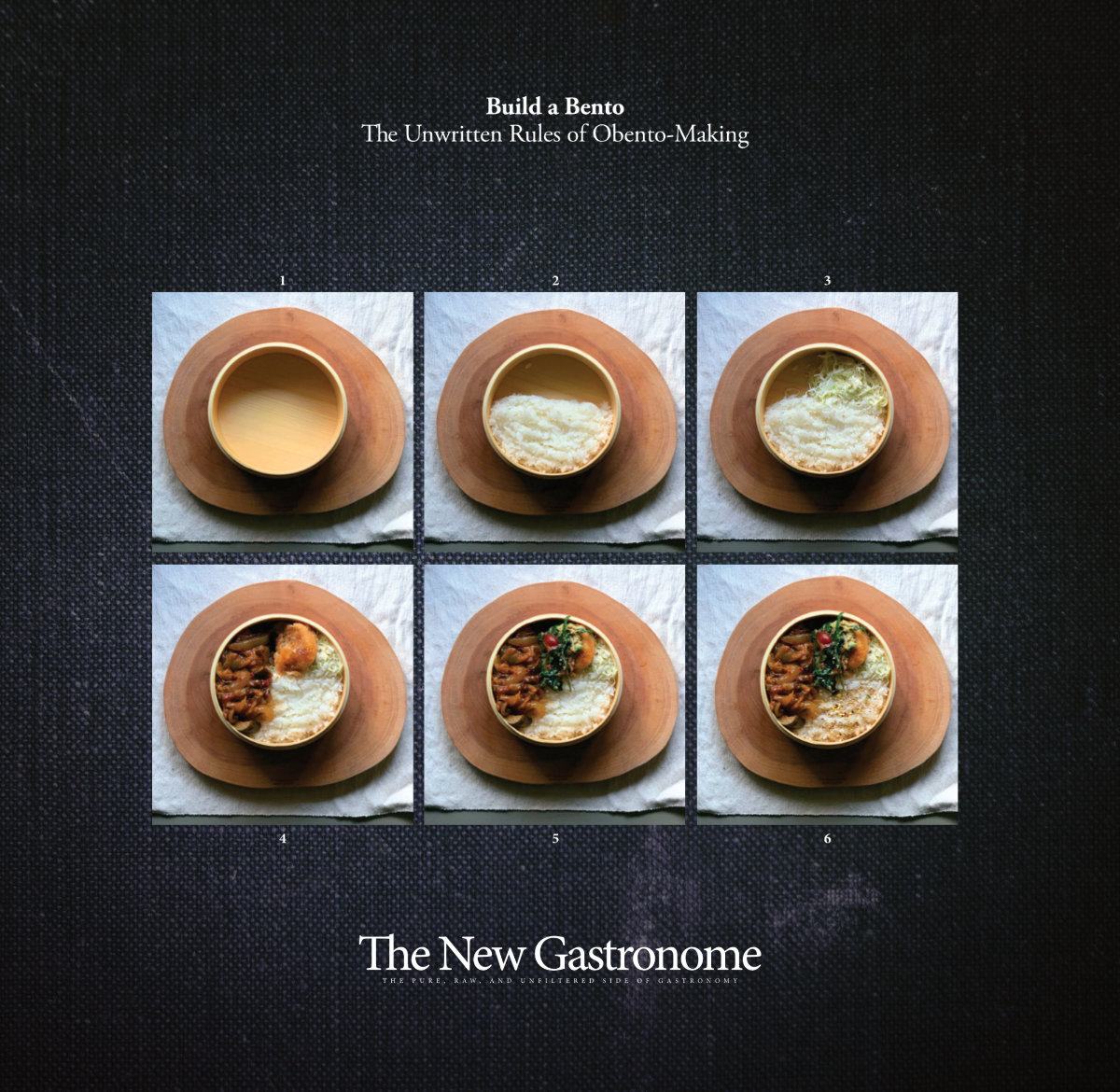

Build a Bento

The Unwritten Rules of Obento-Making

Follow the seasons, so the ingredients have a chance to shine, in both, taste and appearance (in Obento, appearance plays its part)!

Use suitable recipes, so your Obento can be as good as it gets!

Before the bento, cool your ingredients and remove excess liquid, so as not to flood your box. In Japan, rice is an ingredient that cannot be missed. Enriched with vegetables, in its mochi variety or with some spice on the surface, it builds the canvas for your fantastical lunch creations. Remember to let it cool before placing it into your Obento – there shouldn’t be any condensation. Generally, the ingredients should be seasoned and flavoured before being placed in your Obento (in the case of a salad, toss it in a bowl and then place it in

your box)!

The secret to freshness are ingredients that work as antibacterials. Have you ever wondered why an Umeboshi, that red round plum in the middle of the rice, is inserted in most Obento boxes? It is an antibacterial that keeps rice intact without the risk of contamination – it can be replaced by ginger if you don’t have access to Umeboshi!

Follow the order: rice, salad, large ingredients, small ingredients (it all depends on what you want to prepare, of course!), but … Don’t ever forget to have fun!

Photos and Food Styling by ©Eleonora Badellino