The New Gastronome

Not ‘The New Ramen’

A Phở-ntastic Story of Vietnamese History

by Madeline Nguyen

by Madeline Nguyen

Growing up in a Vietnamese American household in California, I ate everything from McDonald’s chicken nuggets to tacos de tripa to raw oysters with fish sauce. Every meal was different and diverse, but phở regularly appeared whenever the temperature dropped or when my sister and I got colds.

From the lightness of phở gà to the crunch of noodles in phở áp chảo and the pink tenderness of phở tái, each version of phở had a place in my life depending on time of year and situation. [1]

I thought I knew everything about phở until I came across a recipe for phở sốt vang (“Red Wine Beef Stew Phở “) in Linh Nguyen’s cookbook, Lemongrass, Ginger, and Mint: Classic Vietnamese Restaurant Favorites at Home.

And after scouring the Vietnamese cookbooks in the school library and asking my mother to check the Vietnamese cookbooks we had at home, it became clear that phở sốt vang wasn’t a part of the phở canon, if such a thing even existed—and if it was included, it was only ever a footnote or mentioned in passing. [2]

Blindsided by this new version of one of my favorite childhood dishes, I decided to make Linh Nguyen’s recipe for phở sốt vang. But even after coming to this decision, the idea of adding wine to phở in any capacity made me extremely uncomfortable. In my mind, red wine in phở was a little too close to boeuf bourguignon, and it called back to the time Vietnam was under French control.

Powering through these concerns – or maybe closing my eyes to them – I made the dish, following each step to a tee, and hoping that the inclusion of Chinese five-spice would make the dish taste more Southeast Asian and less Provençal. After cooking the wine down for an hour, as instructed, the dish barely resembled any version of phở I’d grown up eating. There was no broth to be had – “sophisticated, with many layers of flavors” – or otherwise [I]. It was richer and more stew-like. And although “regular” phở isn’t necessarily a dish I could eat every day for every meal, it is a dish I could eat more often for several days in a row – when my family makes phở, we make enough stock to last several days. The intense spiciness and mulled flavor of phở sốt vang marked it as a one time or one night only dish.

I’d done my best, but what I ended up with was a holiday-appropriate phở that brought to mind Christmas rib roasts and clove-spiced ham. A marker of French imperialism not only in taste, but also in name, with sốt sounding like the Vietnamese-ization of the French word sauce and vang sounding like vin.

However, this French influence goes beyond phở sốt vang and is present in the history of phở bò (beef phở), itself. [3]

Considered by many to be the “national dish” of Vietnam, phở is an integral part of Vietnamese identity. This is especially true for Hanoians—the people whose city is considered by many, if not all, the birthplace of the phở. It is the source of identity and inspiration.

“A marker of French imperialism not only in taste, but also in name, with sốt sounding like the Vietnamese-ization of the French word sauce and vang sounding like vin.“

Community and pride. Respite and nourishment. Writers such as Thach Lam explain that phở is an “all-day food, and a for-all-types-of-people food, especially office workers/public servants, and blue-collar workers” [II].

Although many, if not all of Vietnam, agrees that Hanoi is the birthplace of phở, the rest of the dish’s history remains dubious, with a number of historians and researchers debating and hypothesizing as to when, why, or how phở came to be.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

Citing a number of Vietnamese cookbook authors, scholars, and phở restaurant owners, Alexandra Greeley lists a variety of theories surrounding phở’s origins. Nicole Routhier insists that it “evolved from the Mongolian Hot Pot,” while Ngoc Bich Nguyen says it is a Vietnamese version of a Yunnan goat and noodle soup that was popular along the Chinese-Vietnamese border. Van Le “notes that the ethnic Polynesians who were the earliest settlers in South Vietnam enjoyed a similar soup containing ground pork, tripe, and chicken eggs”. [III]

Hong Lien Vu presents two theories that assume a connection to French imperialism. The first theory establishes phở as a dish that was regularly served to French soldiers that occupied Hanoi during the early twentieth century. The second sets phở as a byproduct of the increased presence and consumption of beef in Vietnam under French occupation. Vu also implies that the word phở comes from the French word, feu, for fire, and creates a narrative in which French soldiers occupying Hanoi at the time would call to phở vendors by yelling feu, in reference to the flame that kept the stock hot. Vendors later adopted the word and would call out the Vietnamese-sounding version of the word, phở. [IV]

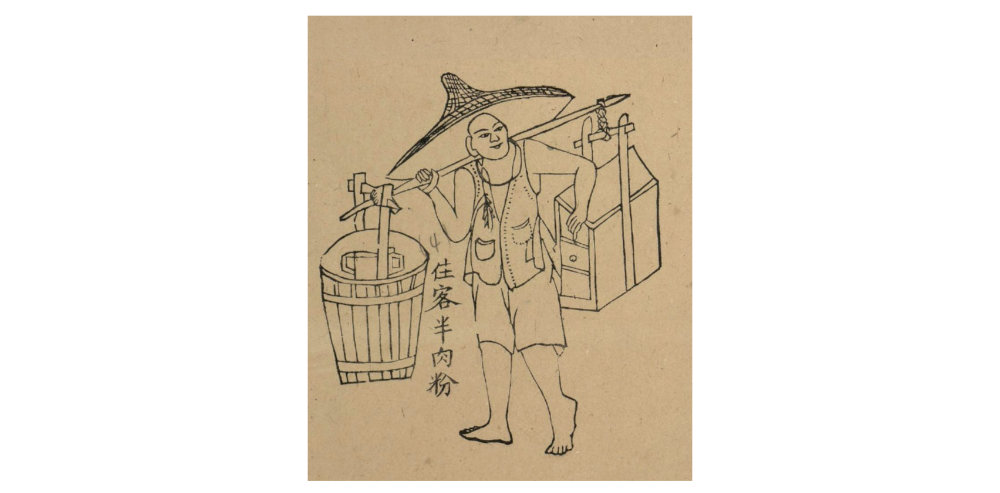

Woodcarving of a phở street vendor. Source: Henri J. Oger, Technique du Peuple Annamite (1908-1910).

While Andrea Nguyen does concede to the impact of the rising popularity of beef as a factor leading to the formation of phở, she and Linh Nguyen reference xao trâu, a dish made with “slices of water-buffalo meat cooked in broth and rice vermicelli” as phở’s predecessor. As beef became more popular and readily available, water buffalo was swapped out and the dish was called ngưu nhục phấn, and as time went on, the name was shortened to phấn. However, the N was eventually dropped because when mispronounced, it sounded like the Vietnamese word for excrement, and thus, the word phở, was born. [V]

Regardless of its mysterious origins and etymology, phở bò, as we know it today – in all its beef variations and toppings – would not exist without French imperialism. Or rather, the demand for beef under French imperialism ultimately led to its normalization, thereby affecting Vietnamese diet and cuisine as a whole. [4]

Before the arrival of the French, beef was not a regular part of the Vietnamese diet because “cows were needed to plow fields and pull carriages”. [VI] But as the number of French settlers increased, so did the demand for beef. Describing the impact of French imperialism on beef-consumption, Hong Lien Vu notes that acceptance of beef by Vietnamese people was gradual and only occurred after several decades under French rule: The cheaper cuts were preferred, such as stewing steak, oxtail and other parts of the animal that were not considered fit for the colonizer’s table. Price was one reason, but taste was another. The Vietnamese like to gnaw on their food, and pork spare ribs and oxtail fitted the bill perfectly. The gelatinous texture of connective tissues once cooked was also much loved by the Việt. [VII]

This preference is also reflected in phở, with beef bones – specifically “knuckle and leg bones that contain marrow” – becoming the basis for the broth in addition to “spices such as star anise, cinnamon sticks and ginger, and roasted onions”. [VII; VIII]

By the early 1930’s, Vietnam became a large consumer and exporter of beef with 500,000 heads being considered a modest-sized herd and beef being shipped throughout Vietnam and to the Philippines. [III] And since then, many beef-centred dishes and meals have become mainstays in Vietnamese cuisine, including bò bảy món, or seven courses of beef.

This connected French history between phở bò and phở sốt vang still does not explain why phở sốt vang hasn’t reached a larger audience in the same way that phở bò and/or phở gà have.

One major reason for its lack of reach is the fact that the dish is a Northern one. After the signing of the Geneva Agreements in 1954, nearly a million northerners moved south following the country’s split and the French departure from the north, bringing northern recipes and culinary traditions with them. [IX]

Northern and southern disagreement over phở ultimately boils down to preference and claims of authenticity.

Phở became widely accepted and popular, but southern adaptations and additions to the dish caused contention that still exists today: People from northern Vietnam prefer their noodles wider than Southerners do and might add lime and fresh chilli to their phở. Southerners, on the other hand, would expect a side dish of lime, chilli, beansprouts, sweet basil and saw-toothed coriander (ngò gai), a herb that looks like blades of grass with jagged edges and tastes slightly sour. [X]

Northern and southern disagreement over phở ultimately boils down to preference and claims of authenticity. The connection between northern phở, authenticity and to an extent, purity, can be seen in the sheer number of Vietnamese restaurants in the United States that are all named “Phở 54”. [XI] Directly referring to the partition of the country after the signing of the Geneva Accords, owners of these establishments are saying that they are purveyors of “real” phở—that is phở made in the way that phở was made before the mass migration to the South.

Before the addition of rock sugar to the broth, beansprouts underneath your noodles, and garnishes on the side. Despite this commitment to northern Vietnamese culinary traditions and recipes, the reality is that the Fall of Saigon meant that a majority of the people fleeing the country were southern and/or northern people who had migrated to the south post-’54, and that the phở that many Vietnamese Americans and non-Vietnamese Americans know today is the southern version, that is the slightly sweeter version that is accompanied by many garnishes. [XII]

In my own house, I ate a mixture of both northern and southern versions of phở —with a sugarless beef broth accompanied by húng quế (Thai basil), tía tô (red perilla or shiso), rau răm (Vietnamese coriander), lime, and chilis. Despite Sriracha being an American invention, it’s found a regular place on my family’s table and on the tables of phở restaurants throughout the US.

And upon reflection, I can see how my own southern roots (my father is from the south; my mother’s family is from the north, but she was born in the south) have affected which Vietnamese foods and flavors I’ve come to expect and know as being real and authentic—that is real and authentic to my own personal history and lived experience as a second generation Vietnamese American.

Writing for Taste, Soleil Ho succinctly explains the impact of migration on Vietnamese American cuisine: “… the enduring image I have of Vietnamese food is only what my parents and grandparents could piece together in their own kitchens. My grandparents and their children cook what is nostalgic for them; in turn, their memories of the past are what I myself crave. The mom-and-pop restaurants I frequent as an adult have rarely challenged this narrative: We all remember and fill in the gaps together.” [XIII]

Like Soleil, my knowledge of Vietnamese food was laid out by my parents and grandparents. That’s not to say I only eat bánh xèo, chả giò, and hủ tiếu. [5] In reality, my taste and that of many Vietnamese peoples (in Vietnam and across the diaspora) spans across the regional cuisines of not only the north and south but also central Vietnam, where the food is spiciest and the dialect is completely different.

In considering authenticity as being defined by personal and inherited history, experience, and culture, I return my thoughts to phở sốt vang. While it may differ completely from my expectation of phở through its lack of broth and its richness, it is still a dish that is authentic to northern Vietnam’s history with French imperialism. The publishing of this exclusively Hanoian recipe in an English-language cookbook featuring pronunciation guides shows that Vietnamese cuisine becoming more popular. I only hope that this rising popularity does not contribute to Vietnamese food becoming a trend. Despite what Bon Appetit claims, phở is not “the new ramen”. [XIV] It’s more than that. Both phở and phở sốt vang are living records of changing tastes, food accessibility, and globalization.

Phở Bò Sốt Vang

(Vietnamese Red Wine Beef Stew with Rice Noodles)

| Beef (sirloin or filet preferred, neck also works) | 750 g |

| Chinese five-spice powder | 1 tbsp |

| Salt | 1 tbsp |

| Fish sauce | 4 tbsp |

| Red wine (I used a Barbera) | 750 ml |

| Yellow onion, chopped | 2 |

| Cloves of garlic, finely minced | 5 |

| Piece of ginger, peeled and minced | 2.5 cm |

| Large tomatoes, semi-frozen, roughly chopped | 1/2 kg |

| Stock or water | 950 ml |

| Star anise, whole | 4 |

| Sticks of cinnamon, whole | 1 |

| Rice noodles or vermicelli | 1/2 kg |

| Olive oil | |

| Black pepper |

*Serves 3-4 people, depending on bowl size

Garnish

Lemon or lime, cut into wedges

Thai Basil (basil could work as a last resort), leaves left whole

Mint, larger leaves are roughly torn or chopped

Cilantro, de-stemmed

Scallions, thinly sliced on the bias

Bird’s eye chillies, thinly sliced on the bias

Method

First, trim the beef of fat. Cut into 2.5 cm cubes. Marinate in five-spice, red wine, black pepper, tbsp of fish sauce, and 1 tbsp of olive oil for 30 minutes to one hour. Heat a heavy-bottomed large pot or Dutch oven over a high flame. Add 2 tbsp of olive oil, garlic and ginger. Stir-fry until lightly golden and fragrant. Be careful not to burn it. Then, lower the heat. Add the onions and stir-fry until semi-translucent, add 2 of your tomatoes and a dash of fish sauce, stirring until it becomes a paste. Remove from pot and set aside.

Raise the heat again. Swirl another 3 tbsp of olive oil into the pot and begin searing the beef in small batches. Return the tomato paste to the pot, mixing it with the beef jus. Add the remaining wine, tomatoes, fish sauce, four cups of water, cinnamon, and star anise. Bring to a boil, before lowering it to a simmer for a minimum of 1.5 hours (ideal would be 2-3 hours, depending on the cut of beef used). Stir occasionally to make sure nothing sticks to the bottom.

While your soup simmers, boil water and cook your rice noodles according to the packaging instructions. Add a teaspoon of a flavorless oil to prevent clumping. Unlike pasta, you do not want your rice noodles to be al dente at all, so if they’re not soft at the end of the suggested cooking time, wait another 2-3 minutes. Then, distribute your noodles between two bowls. Ladle the stock, meat, and tomatoes over it — make sure to fish out the whole spices. Serve immediately with lemon and garnish on the side. Season to taste using fish sauce and black pepper.

*Adapted from Linh Nguyen’s recipe for “Red Wine Beef Stew Phở (Phở Sốt Vang)” in Lemongrass, Ginger and Mint Vietnamese Cookbook: Classic Vietnamese Street Food Made at Home (2017)

Notes:

[1] Phở gà is phở with chicken and a chicken-based stock. Phở áp chảo is a stir-fry, in which the specific type of noodles used in phở called bánh phở, are pan-fried until crispy and topped with a sauce made with beef and vegetables. Phở tái is a beef phở in which thinly sliced pieces of raw beef laid on top of the noodles before boiling stock is poured on top. The stock then lightly cooks the beef leaving it pink in the center.

[2] In The Pho Cookbook: Easy to Adventurous Recipes for Vietnam’s Favorite Soup and Noodles, Andrea Nguyen describes phở sốt vang as “phở with beef stewed in white wine,” while Linh Nguyen says to cook hers in red wine.

[3] Phở bò is considered by most to be more authentic than phở gà (chicken phở)

[4] The beef variations I refer to include sách (tripe), bò viên (meatballs), etc.

[5] Bánh xèo is a savory turmeric crêpe- or pancake-like dish. Chả giò are deep-fried spring rolls (not egg rolls because they use rice paper for the wrapper). Hủ tiếu is another noodle-soup dish with a pork-based broth. All of these dishes are native to the southern part of Vietnam.

Bibliography:

[I]Nguyen, L. (2017). Lemongrass, Ginger, and Mint: Classic Vietnamese Restaurant Favorites at Home. Berkeley, CA: Rockridge Press. p.114

[II]Lam, T. (1943). Quà Hà Nội. In Hà Nội băm sáu phố phường. Retrieved November 24, 2018

[III]Greeley, A. (2002). Phở: The Vietnamese Addiction. Gastronomica, 2(1), 80-83. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

[IV]Vu, H. L. (2016). Rice and baguette: A history of food in Vietnam. London: Reaktion Books. p.126

[V] Nguyen, A. (2017). The Pho Cookbook: Easy to Adventurous Recipes for Vietnam’s Favorite Soup and Noodles. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p.4

[VI]Nguyen, L. (2017). Lemongrass, Ginger, and Mint: Classic Vietnamese Restaurant Favorites at Home. Berkeley, CA: Rockridge Press. p.102

[VII]Vu, H. L. (2016). Rice and baguette: A history of food in Vietnam. London: Reaktion Books. p.124-125

[VIII]Nguyen, A. (2006). Into the Vietnamese kitchen: Treasured foodways, modern flavors. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p.209-211

[IX]Nguyen, L. (2017). Lemongrass, Ginger, and Mint: Classic Vietnamese Restaurant Favorites at Home. Berkeley, CA: Rockridge Press. p.103

[X]Vu, H. L. (2016). Rice and baguette: A history of food in Vietnam. London: Reaktion Books. p.125

[XI]Nguyen, A. (2017). The Pho Cookbook: Easy to Adventurous Recipes for Vietnam’s Favorite Soup and Noodles. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. p.6

[XII]Ho, S. (2018, November 20). Why Is Vietnamese Food in America Frozen in the 1970s? para.3 Retrieved November 23, 2018.

[XIII]Ho, S. (2018, November 20). Why Is Vietnamese Food in America Frozen in the 1970s? para.4 Retrieved November 23, 2018.

[XIV]Yam, K. (2016, September 15). Why The Outrage Over Bon Appétit’s Pho Article Is Completely Justified. para.12 Retrieved November 21, 2018.

Coverphoto: © Aarón Gómez Figueroa