The New Gastronome

Myths & Stories about Breastmilk

by Santina Cerino

by Santina Cerino

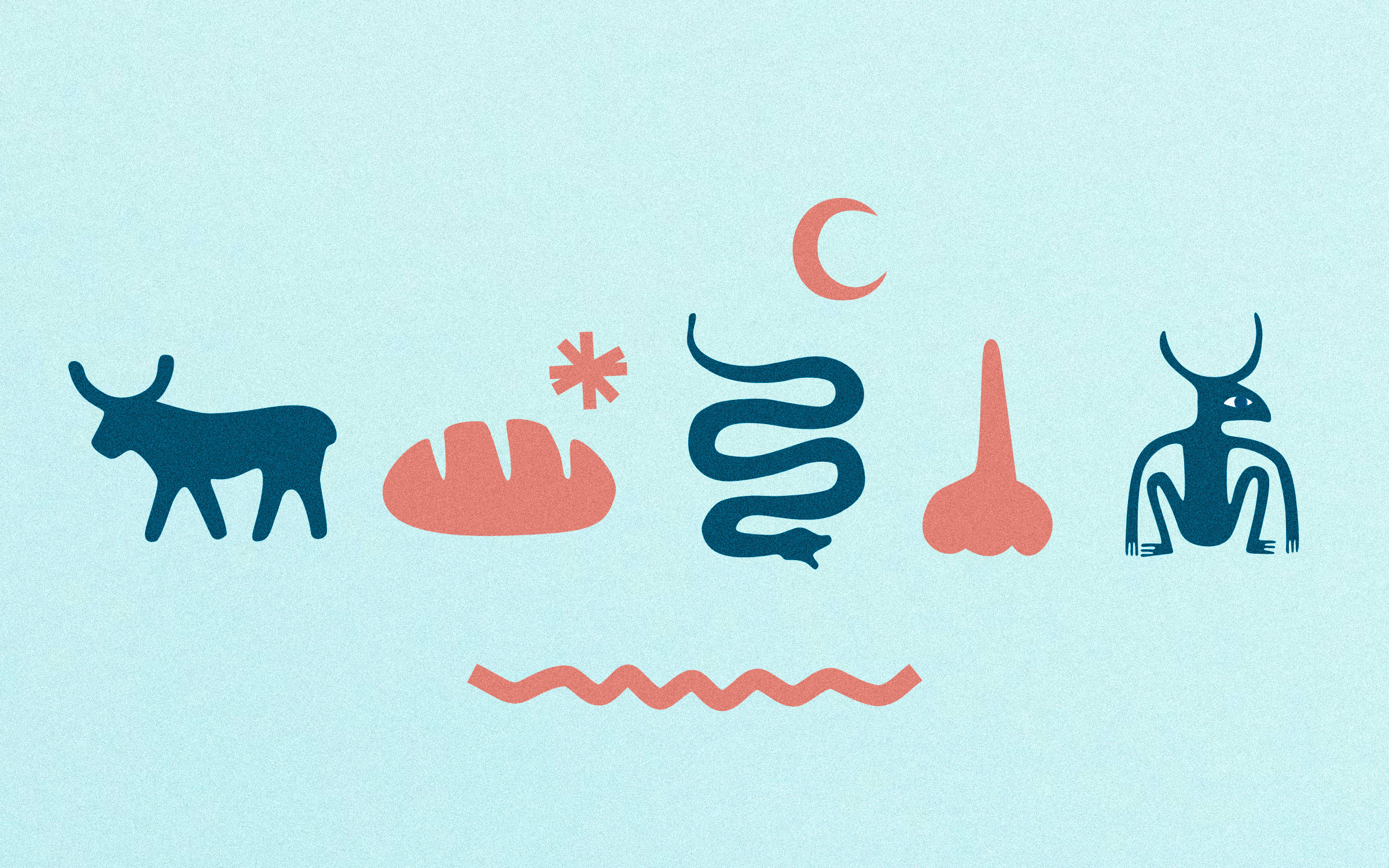

What is breast milk? It is everyone’s first food, a rich source of nutrients and antibodies that help protect against diseases. It’s also something that has an incredible history—one that’s been revered for its healing properties for thousands of years. You can call it “the food of the Gods” or”the most sacred thing in the Universe.” You can say that it’s been used for medicine, food and beauty products throughout history. And you’d be right on all counts! But how much do you really know about this sacred elixir? Let’s dive into the facts, myths and stories about the essence of life.

#1

The first child-care worker and doctor in history, Sorano of Ephesus, who lived in Rome in the first half of the second Century of the Christian era, divulged the belief that the newborn baby for the first two days of life should be fed only with boiled honey. He advised mothers to wait another 20 days before breastfeeding while providing the babies with milk from another woman because he was convinced that the milk of the first days was indigestible and unsuitable for newborns. He advised mothers to avoid sharp-smelling indigestible foods, such as onions and garlic and to eat very light bread and white meats instead. In front of the impossibility of starting or continuing breastfeeding, he suggested resorting to a wet nurse who chose the following precise and rigid canons: physical and moral. He also indicated that exercising their upper body would help the milk flow copiously to their breasts.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

#2

The work of the wet nurse, central to the history of women from the Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century, has seen particular intertwining and developments with the institutional, economic and social reality of Tuscany. This activity was traditionally carried out as an act of solidarity among members of the same community or at public hospitals to assist abandoned children. In the second half of the 19th Century and in the first half of the 20th Century, it became a job that led many women to leave their newborn children to emigrate to an Italian or foreign city to breastfeed someone else’s child. The Tuscan wet nurses were highly sought after and well-paid thanks to their excellent physical and health conditions combined with their knowledge of the spoken Italian language. These characteristics privileged their way into wealthy families’ homes that hosted them: the natural mothers were freed from the “fatigue” of breastfeeding.

#3

The woman living in the Langhe area, Piedmont, was a balia fresca, balia da lac meaning fresh milk wet nurse who entrusted her newborn baby to the care and breast of her neighbor, who fed them the same milk as her own infant. It was common to share milk, borrow and exchange it; in fact, in the peasant world, the same happened with other laborers as well, and it remained a common habit until a few decades ago. A custom dating back to the Medieval ages, when lending labor time was commonplace, it couldn’t be monetized since it was considered God’s belonging. If the woman ran out of milk but had to raise the children, she would become a balia sucia meaning a wet nurse without milk, a dry mother, a definition that in the peasant world had a negative connotation.

#4

Sometimes, the wet nurses from the Langhe area offered their milk to French families, where they were called nunù. According to the contract stipulated, men could not visit their wives during the entire breastfeeding process because a possible pregnancy would interrupt the regular flow of the milk chosen to feed the noble infant. A birth control strategy that is not so much attributable to the real risk of pregnancy but to the widespread knowledge regarding coitus “that could disturb the woman’s blood and consequently her milk.” Due to this link between milk and sperm, the wet nurse had to stop her duty long enough after sexual intercourse before getting back to breastfeeding.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

#5

If a woman lost her child and did not want to take a ventürin, an orphan, she had to recourse to a person specialized in sucking the milk, whose nickname was ciucialait, milk sucker. The name comes after their ability to do it delicately. They were compensated with natural gifts such as eggs and other farmhouse products and the sucked milk, which was precious nourishment. When it wasn’t possible to rely on the ciucialat , the father-in-law would fulfill this task since he had experience with it. In any case, he could enjoy this precious food that belonged to the household, that was not wasted. On the other hand, breast milk’s therapeutic and magical power is part of the myth of the fountain of youth: the food connected to youth and fertility that nourishes and rejuvenates man’s old age.

#6

The entry into life and society required the passage from the mother’s breast to the breast of the family. It was the most important and most difficult moment. So challenging that its danger was already perceived by the primitives: armed men guarded the door of the house, and with various bells, they kept wicked spirits away at the moment of childbirth. At the time of birth, the umbilical cord was cut further down in the boy to strengthen his virility and was the subject of many other rituals. Trotula, a medieval midwife, recommended “severing the four-finger cord from the belly and doing this very carefully for the male, because the penis will be longer depending on the distance. Then, it was buried on the house’s threshold, at the foot of a tree, by the sea, or abandoned to running waters if you wanted a son with singing talents or where water dripped so that the mother’s milk flowed abundantly for sympathetic magic. In Rome, the newborn was placed on the ground by the nurse who had previously confirmed their health conditions; the pater familias could recognize him or her by lifting them up, invoking the goddess Levana and keeping them in his arms. If the newborn was a female, the pater familias had to order to breastfeed her to welcome her to the family. In Metamorphosis, in one of his digressions, he tells of a husband who recommends that his pregnant wife kill the baby if it is female. The woman, disobeying, secretly entrusts the baby to some neighbors. A similar order, always given by a man, is testified to in a papyrus by Ossirinco: “If it is a male, raise it; if it is female, uncover it.”

#7

In the ancient world, and then in the modern one, in the humanistic field, powers of apotropaic magic towards their protégés were also attributed to midwives and nurses. Rumina protected, as her name implies – ruma (breast) – Edula, the first food after the weaning phase. Mother’s milk, an intense symbol of new life, was considered in ancient Egypt to be the very substance of the embryo. For this reason, in a strong desire for rebirth, the Egyptian lamenters showed their bare breasts, a custom still alive in the past Century during the Lucanian lamentations, one of the most significant rites of mourning. In the Egyptian and Etruscan world, milk was considered a source of life and health. Also, in the Jewish world, more than one passage from the Old Testament symbolizes the fruitfulness of the promised land with the definition of “land where milk and honey flow.” In Greek culture, the white element was sometimes opposed, with a negative meaning, to the wine that gave strength and virility.

A. D V. E. R. T. I. S. I. N. G

#8

If hospitalization guarantees the woman and the newborn’s safety from real dangers, it cannot symbolically protect them against dark forces which humans still believe in. For this reason, divination, shielding, apotropaic and therapeutic practices often occur from conception to childbirth and then to breastfeeding. Ten days before giving birth, a drop of milk was squeezed and poured into a cup of water: if it went down to the bottom, it would have heralded a boy; if it remained afloat, a girl. The sex of the girl was sprinkled, especially in the region of Campania, with sugar – meaning that the art of attracting and seducing is suitable for women -; in the lower Salento area, the tiny baby’s nipples were squeezed by the grandmother so that the female child, once a mother, would have plenty of milk. The figure of the witch is very present in classical literature, where we see her operating in recollection rites or in those of black magic. The belief that the evil companies squeezed poisoned milk into the little mouths of the little ones was already reported by ancient writers. Opinions differ on the nature and role of goblins and munacielli; even in the modern world, it was said that goblins tormented new mothers by slowing the flow of milk and removing the baby from the cradle.

#9

To protect themselves from the hexes and evil, various amulets, such as those of red coral and the “eye of Saint Lucia” consisting of the operculum of a shell, was tied in silver or hung on a red ribbon, a color that since ancient times had apotropaic virtues. Moreover, coral ornaments, such as brooches or earrings, were given to wet nurses to protect their health: any changes in its beautiful color, a sign that this material absorbed the scents of the human body, would have denounced diseases with negative consequences for the excellent quality of the milk. The mothers of Salento would wear, already during the pregnancy, a milk stone consisting of a fragment of flint and, in the province of Frosinone, mothers also went to the cave of Sant’Angelo, where, after having scraped a little of it from its walls of rubble and possessing it carefully enclosed in a host, they swallowed it to favor the abundant flow of the precious food. For the child not to regurgitate the too-substantial milk, he had to wear around his neck a broken jug shard found by accident. The milk could be scarce or even none, so women, after giving birth, ate rue, a very bitter herb, to keep witches away. Mothers also did not sweep to avoid any dirt from getting into the milky duct.

The opinions expressed in the articles of this magazine do not necessarily represent the views of The New Gastronome and The University of Gastronomic Sciences of Pollenzo.